Predictably bad predictions

Predicting AI's development is challenging, strengthening the case for systematic diversification

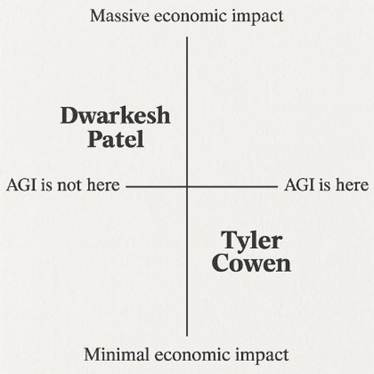

The advent of AI has led to a field day for futurologists seeking to predict the potential impact of AI on tomorrow’s economy & society. TBPN’s John Coogan summarized the AGI progress vs impact debate with this handy two by two:

Platform shifts broaden the spectrum of possible outcomes: opportunity for high upside, but also amplified risk.

There is consensus that AI is a big deal. But no-one knows exactly how far & how fast the technology will develop. This creates substantial financial (& career) risk in being a traditional VC these days, making just 1-2 investments per year.

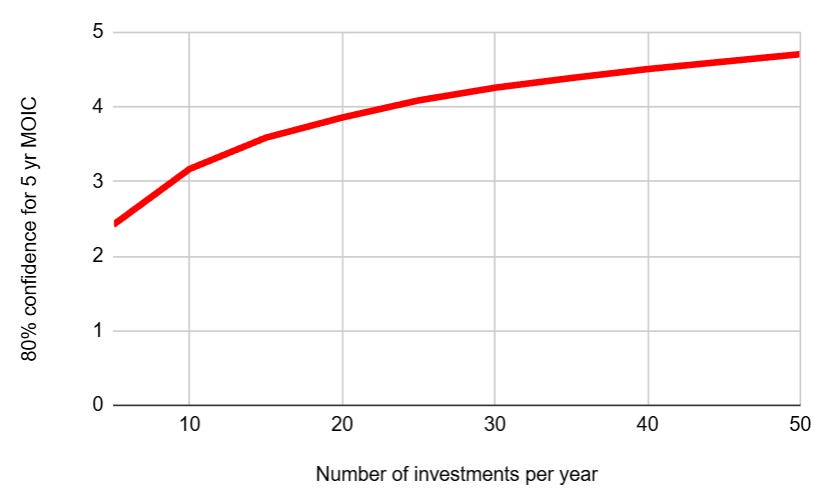

It is precisely at these moments why a highly diversified model such as SignalRank’s should appeal to allocators. We are aiming to make 30 investments per year at scale, with our structure also offering high vintage diversification. One investment today provides an investor with access to both our historic & future vintages.

This post considers the difficulty in predicting the future, how this applies to VC and then suggests that SignalRank’s systematic & diversified approach can offset some of these challenges.

The challenge with predicting the future

The future is of course unknowable, reflecting more about present concerns than anything else. The only thing we can be certain of is that most predictions will be wrong.

This is the topic of this book, which was the inspiration for this post, which looks at the history of predictions about the future.

It can be fun to look back at prior predictions, although this does give the false impression of wisdom just by living later. There is a risk of unfairly inflicting on prior generations “the enormous condescension of posterity,” to borrow a phrase from the historian EP Thompson.

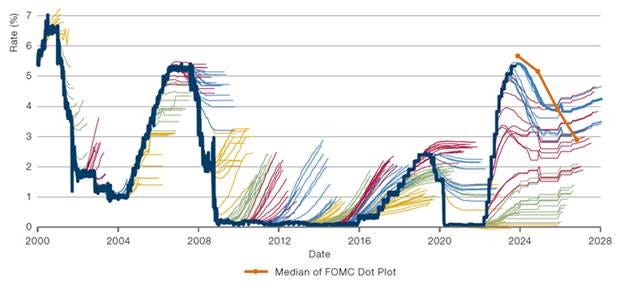

There are lots of good examples of the futility of predicting the future. Figure 1 is perhaps the most compelling chart to make the point, demonstrating effective Fed Funds rate versus market expectations.

Figure 1. Effective Fed Funds rate versus market expectations (from Man Group)

Another great memo on predicting the future comes from Donald Rumsfeld of all people. He wrote this one page memo, just six months before 9/11: “All of which is to say that I’m not sure what 2010 will look like, but I’m sure that it will be very little like we expect, so we should plan accordingly.”

This is also quite a good list of the most inaccurate technology predictions in the last 150 years.

VCs trying to predict the future

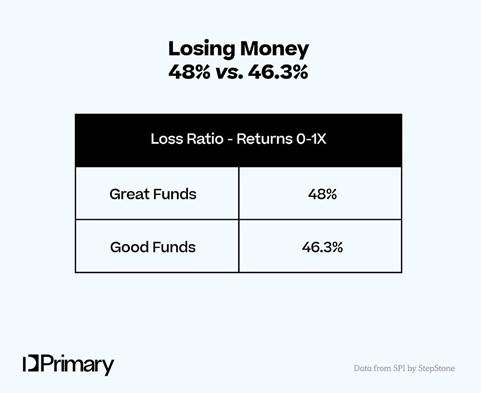

Venture capital is a high variance asset class with high returns and high loss ratios. Even where there is platform stability (as during the mobile & cloud era from 2006-22), it is challenging to identify & back the right opportunities.

In fact, the perverse thing about VC is that the best funds have higher loss ratios. Here’s some data from StepStone and Primary:

Zeroes are expected. Daybreak’s Rex Woodbury talks about how “zeroes that could have been fund-returners should be celebrated as good swings: this is a business of home-runs, not second-base hits.”

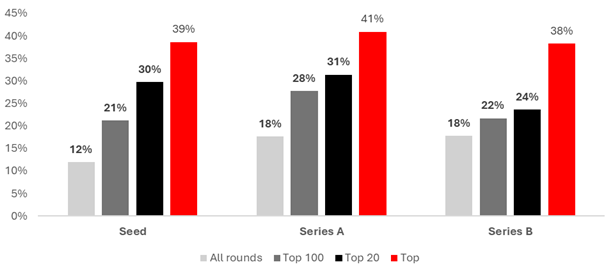

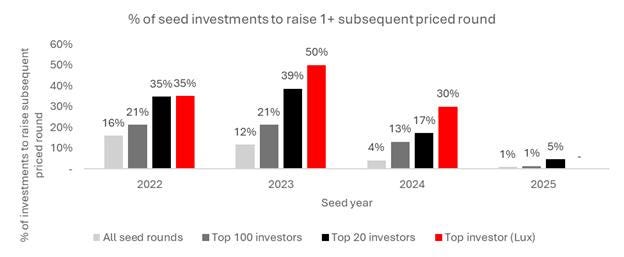

We also ran some analysis to consider how firms have performed in the post ZIRP era. We see that only 30% of seed investments since 2022 by the top 20 seed managers (per our model) have raised a subsequent priced round (or 12% for all seed managers).

If we interrogate this further by looking at the cohort by cohort data, the picture is not much better. Only 35% of 2022 seed investments by the top 20 investors have raised a subsequent priced round.

In short, VC is a really hard business.

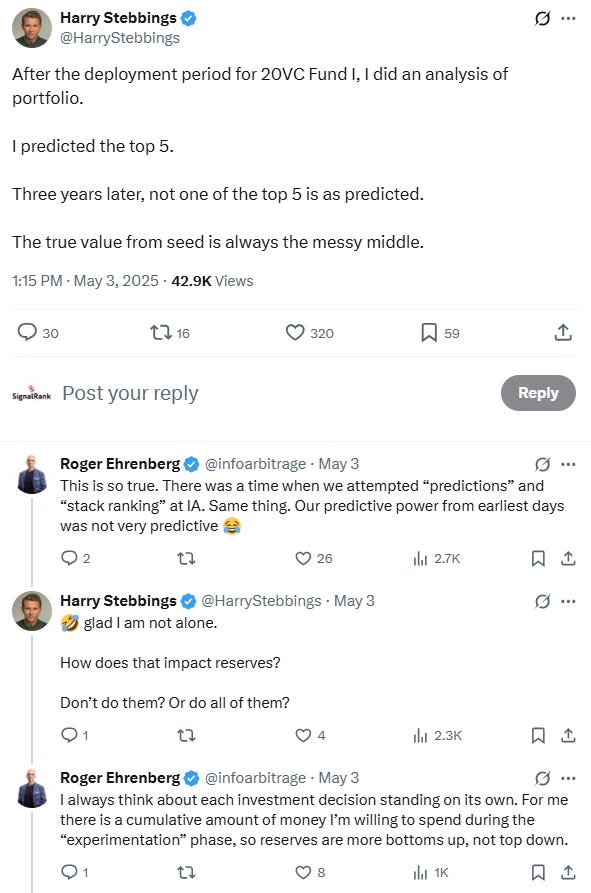

Even when VCs are already investors in a startup, it is challenging to predict outcomes. This can lead to significant misallocation of precious reserve capital into portfolio companies that will not return the fund. Some humility from 20VC’s Harry Stebbings here:

How a systematic approach can help

Individual bias reduction

This paper evidences that VCs are making “predictably bad” investments by over weighting data on founder traits. This is but one example of cognitive bias that can lead to significant misallocation of capital.

A systematic approach should reduce some of these individual biases. By requiring a company to have been backed by at least three world class investors across three separate rounds, our model reduces reliance on any one individual. Our approach also effectively eliminates any biases internally within our team, by giving the algorithm primacy in decision-making.

A caveat is that any new system will of course bring a new set of potential biases, including data bias, temporal anchoring bias, access bias, survivor bias and others. Nevertheless, in aggregate, our backtest suggests that this system should consistently deliver top quartile performance across vintages.

Diversification

Diversification is the only free lunch in finance.

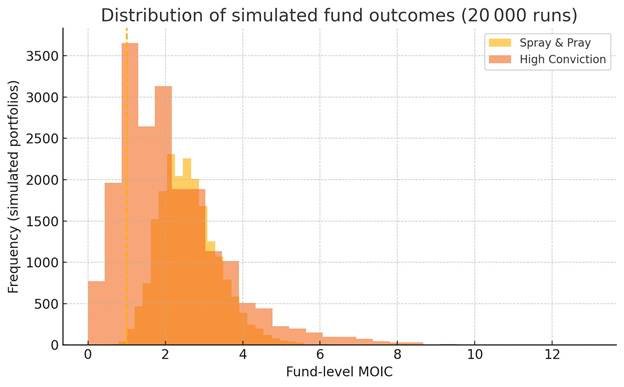

SignalRank is a classic index-like strategy in that we are sector, geographically, manager & vintage agnostic. With a target 30 investments per year, this should lead to high diversification which should lead to more consistent returns.

Our Monte Carlo simulations show how our expected 5 yr MOIC per annual cohort increase to above 4.0x with 80% confidence once 30+ investments are made per year.

We have argued before here that vintage diversification is also particularly underrated during times of rapid change.

More recently, Equidam’s Dan Gray (as well as Carta’s Peter Walker) have been arguing here about how VCs should be aiming for higher diversification.

A final thought - some predictions of our own

Despite all this, we couldn’t resist making a few predictions of our own, publishing our view of what the venture capital ecosystem will look like in 2030.

Let’s see how wrong we are in 2030...