Vintage diversification is an underrated free lunch

Harry Markovitz: "Diversification is the only free lunch in investing"

NVPERS, Nevada’s public employees’ pension fund, has a killer investment strategy. One person, Steve Edmundson, manages north of $60bn, with a 100% indexing strategy across eight managers (Figure 1). Cue lots of questions about what exactly Steve does all day (answer: nothing).

NVPERS has performed admirably with 9.4% annualized returns since inception (vs 9.2% for their benchmark market return; Figure 2). This performance is in-line with top performing US endowments who typically adopt more complex strategies.

So why do the Yales & Harvards of the world bother? Why allocate outsized amounts to alternatives? What is the point of venture capital in an allocator’s portfolio?

Figure 1. NVPERS managers as at 30 June 2024

Figure 2. NVPERS returns as at 30 June 2024

It is time to revisit the myth of the Yale model, crafted by the legendary CIO David Swensen, to understand why it was revolutionary at the time, why it has been broadly adopted by endowments and why it is now being pushed onto retail investors. We can then drill into the role of VC within an allocator’s portfolio.

We know that most VCs do not outperform the S&P. It is a challenging asset class for the average investor. In fact, we are going to argue that the point of investing into venture capital today is as much diversification as it is an expectation for outsized returns. Diversification from equities into alternatives allows risk to be reduced without sacrificing expected return. In particular, the illiquidity of the asset class provides temporal diversification for allocators.

David Swensen revisited

The consensus on asset allocation today is built on the foundations laid by the University of Chicago’s Harry Markowitz in 1952 with his portfolio optimization techniques branded as Modern Portfolio Theory. The idea is to achieve the highest expected return for any given level of risk, by balancing asset allocation based on expected returns and covariances (correlations), thereby maximizing returns while minimizing risk within a portfolio.

In essence, this boiled down to holding 60% stocks and 40% bonds for most investors (where the low or negative correlation between stocks and bonds balances a portfolio’s returns). By diversifying into less correlated assets and investing into higher return-per-unit-of-risk assets, investors can improve their returns. Figure 3 demonstrates how the introduction of less correlated and high potential alternatives can drive superior returns relative to the 60/40 model.

Figure 3. Efficient frontier

This was the essence of the David Swensen model. He aimed to diversify away from US equity market risk. The core of the “Yale Model” which became the gold standard for endowments is as follows (in Swensen’s words in Pioneering Portfolio Management, summarized by Ted Seides here):

Equity bias: “Sensible investors approach markets with a strong equity bias, since accepting the risk of owning equities rewards long-term investors with higher returns.”

Diversification: “Significant concentration in a single asset class poses extraordinary risk to portfolio assets. Portfolio diversification provides investors with a “free lunch,” since risk can be reduced without sacrificing expected return.”

Alignment of Interest: “Nearly every aspect of fund management suffers from decisions made in the self-interest of the agents at the expense of the best interest of the principals. By evaluating each participant involved in investment activities with a skeptical attitude, fiduciaries increase the likelihood of avoiding or mitigating the most serious principal-agent conflicts.” Swensen’s advice is to keep it simple and stick with passive, low-fee index funds wherever possible.

Search for inefficiency: Focus on asset classes with a wide dispersion between top and bottom performers and employ external managers to exploit opportunities.

This approach necessarily required tilting towards darker corners of the asset management matrix, in overlooked, less efficient and more illiquid asset classes. He accepted that illiquidity is “the inevitable cousin of diversification and high-return investment opportunities.” Given Yale’s endowment set up, he recognized that he could focus on assets with a long duration and locked-up capital.

He also sought to take advantage of market inefficiency that led to attractive prices. The underpricing of private assets more than compensated for the lack of liquidity to drive strong risk-adjusted returns. The private market is substantially more efficient today than when Swensen started his strategy.

So how did he do? Swensen turned Yale into one of the largest endowments in the world.

Figure 4. Size of Yale endowment over time ($bn)

Figure 5. Yale asset allocation over time (% of assets per allocation)

Many endowments and institutions have sought to replicate Swensen’s approach, driven by the belief that private markets can deliver superior returns relative to traditional investments. KKR and others are similarly arguing that high net worth individuals should seek to increase their allocations to alternatives. Calpers is now aiming for 40% allocation to PE & private credit.

Swensen actually advised against this eventuality. He recognized that his approach was only suitable for the most sophisticated investors: “in the absence of a truly superior fund selection skills (or extraordinary luck) investors should stay far, far away from private equity investments.” He argued that investors are largely better off just investing in the public markets, especially given the higher risk and higher illiquidity.

Not all diversification is equal

Private equity (including VC) is no longer the dark backwater of the asset management industry. The price inefficiencies identified by Swensen are harder to come by today than when he first implemented his strategy. This is an argument that the industry should anticipate returns to become more normalized (i.e. lower).

Nevertheless, allocating to alternatives could still provide diversification which should increase returns without increasing risk. But does PE & VC actually deliver on this diversification ideal?

If you measure diversification by correlation to equity risk, the answer is no. Swensen himself argued that “because of the strong fundamental links between private equity investments and marketable equities, private equity provides limited diversification to investors.”

AQR has this helpful table (Figure 6) to demonstrate how private equity (including VC) is the most correlated alternative asset class to global equities. Full paper is here.

Figure 6. AQR’s correlation analysis between different asset classes

AQR goes even further to argue that, within a supposedly “diversified” portfolio with only 40% global equitie exposure, 95% of the risk exposure is attributable to equity & credit risk factors (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Mapping asset class allocations to underlying risk factors

Diversification across asset classes does not necessarily mean diversification across factor exposures. OK, does private equity (including VC) provide any other diversification benefits?

Temporal diversification

Private equity / venture capital enables greater temporal diversification relative to more liquid alternatives & traditional portfolios. This is an underrated source of diversification for investors. This diversification manifests itself in various ways:

Capital deployment has greater independence from public market cycles. Technology cycles do not move in perfect synchronization with financial cycles. See the capital injection into AI last year during a time of high inflation and higher interest rates (relative to the preceding post financial crisis period). Chamath Palihapitiya has this helpful chart to demonstrate the founding of tech companies is not hugely correlated to interest rates.

Illiquidity compounds returns and mitigates timing risks We discussed here how illiquidity is a feature, not a bug. Illiquidity enables the compounding of returns over time, preventing investors from selling prior to locking in the power law gains. While investment timing is diversified, returns rely on favorable economic conditions which tend to be more aligned with broader market cycles. Distributions today are made from investments made 10+ years ago.

Multi-vintage exposure Consistent investment pace by LPs increases exposure to different economic, technological and market conditions. This also increases the probability of an LP hitting a golden vintage. PitchBook recently showed that IRRs improved to 12% for ‘slower’ deployment by VCs (compared to 10% for ‘faster’ deployment). In addition, capital calls by managers takes place over a 2-5 year investment period, reducing the risk of investing all the capital at a peak or trough.

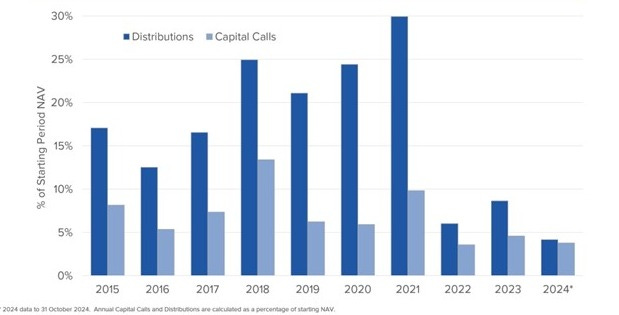

This value of temporal diversification was effectively illustrated in a recent post here by Vencap’s David Clark. This chart demonstrates how VenCap, a longstanding investor in first class VC funds, consistently deploys into each vintage while distributions are sawtooth shaped.

Figure 8. VenCap’s annual distributions vs capital calls (% of starting NAV)

Therefore, what?

This gem above from Kyla Scanlon may be of one the all-time great memes: gaining an edge in investing is hard. Investing properly over the long term is really hard. A 100% indexed strategy, as exemplified by NVPERS, is one approach to building a diversified portfolio. It has delivered for NVPERS over time. Yet David Swensen demonstrated that a greater allocation to PE/VC can provide additional diversification to bring a portfolio higher up on the efficient frontier.

We have argued here that temporal diversification is an underrated element of this diversification.

When it comes to SignalRank specifically, our permanent capital structure provides a spin on temporal diversification. Our investors acquire preferred shares which gives an investor their pro rata ownership of the existing historic portfolio (at current NAV) as well as any future investments. There should be minimal vintage risk with an always-on investment strategy. Again, the reinvestment of returns should compound returns which itself will provide natural temporal diversification. Temporal diversification is built into our structure.