It’s hard not to be romantic about venture capital (to paraphrase Billy Beane from Moneyball). Investors love the image of the wizened VC unearthing two entrepreneurs working on the next big thing in their Palo Alto garage, providing seed capital and sage advice before culminating in the obligatory opening bell photo at the NYSE.

Core to this VC lore is the concept of the power law. It is well understood that most companies fail, and that most returns come from a small number of companies. In fact, the power law itself has taken on mythical status within the industry.

One could go so far as to argue that the whole framing of the VC industry is now based on the power law. The power law’s perceived uniqueness to venture capital is projected onto allocators. VCs hold an idealized view of the industry as a “special” institutional asset class where a small number of winners drive all returns.

Yet we will show here how Pareto distributions (cleverly rebranded as the “power law”) are not unique to VC in institutional financial markets.

To the extent that VC is a unique institutional asset class, it is in its illiquidity. (To be crystal clear, by illiquidity, we are using short hand for very long holding periods which are followed ultimately by returning capital to LPs). Very few investments exit each year from M&A or IPO. Since 2021, we have been in a particularly fallow period. Hence the VC thinkbois crowing on X about the end of VC as we know it.

Yet it is only when you view the asset class through the prism of illiquidity, and not power law returns, that one could argue for VC having a special place in institutional allocators’ portfolios. It is precisely because VC is illiquid (and not despite the illiquidity) that VC is attractive.

The high growth of early stage companies compounds over time into stellar IRRs because VCs have no option but to hold their positions. In response to Carta’s much shared report on the state of VC performance, Vencap’s David Clark showed that a fund with eventual 12x DPI had zero DPI by Year 5 (echoed today by Sapphire’s Beezer Clarkson who shows average funds get to 1x DPI by Year 8).

LPs know and appreciate that VC is illiquid. To be clear, LPs obviously want a return on capital and require DPI. But they do not have a problem with illiquidity per se. It is the unpredictability of this illiquidity that is the underlying issue in the industry.

Let’s unpack this.

The Pareto principle is a universal law

Before we look at liquidity, let’s review the commonly held assumption that the power law is the defining & unique feature of venture capital.

The power law is undoubtedly a key characteristic of venture capital. Ben Horowitz famously remarked that 97% of venture capital returns in any given year come from 15 investments. But the power law is not unique to venture capital.

The Pareto Principle (or “80/20 rule”, or “power law”) illustrates that 80% of effects arise from 20% causes. This model was first observed by the Italian-born economist Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923), who noted that a relative few people in Italy held the majority of the wealth & land. Pareto developed logarithmic mathematical models to describe this non-uniform distribution of wealth.

It was not until the 1950s that a management consultant called Joseph Juran re-discovered Pareto’s work, and he pointed out that Pareto’s principle was indeed a “universal” law which applied to an astounding variety of situations. Examples of phenomena with power laws include populations of cities, frequency of use of words, sales of books and solar flare intensity.

Pareto in public markets

Public markets also exhibit strong power law characteristics. This flies in the face of standard finance theory, especially the Efficiency Market Hypothesis which assumes at any given time a stock price fully reflects all available information about that particular stock. Multiple studies have now shown that price changes in the stock market follow a distribution that exhibits excess kurtosis, with fatter tails than in a normal distribution (Mauboussin, 2002; Mantegna and Stanley, 1995; Pagan, 1996; Lux, 2006).

Ben Graham, the godfather of value investing & author of The Intelligent Investor, admitted that he himself made more from one investment in a growth stock (GEICO, 500x+) which broke all his value investing rules than all of his other investments combined. His philosophical successors, Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, have also commented that excluding the top 15 of their investments over 70+ years would give them unremarkable track records.

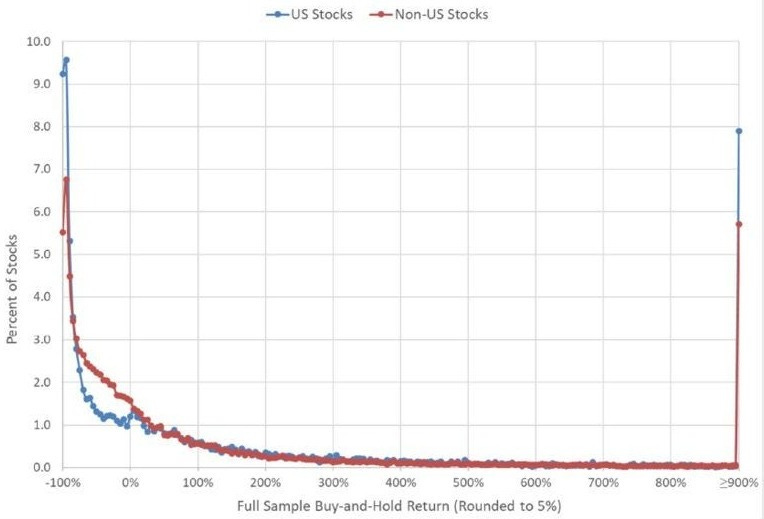

A fascinating longitudinal study demonstrated exactly how powerful the Pareto principle is in public markets. Bessimbinder found just 86 stocks accounted for half of all wealth creation (above Treasury bills) in the U.S. stock market going back to 1926. All of the wealth creation in that time came from just 4% of stocks (1,092 companies). 58% of stocks failed to beat T-bill returns over their lives.

Figure 1. Distribution of buy-and-hold returns from US stocks, 1926-2019

Bessimbinder’s study (Figure 1.) helps explain the success of passive index strategies, as active strategies, which tend to be less diversified, mostly underperform. If indices outperform active managers in power law distributed public markets, surely the same logic should apply to private markets?

This demonstration that power law distributions are not unique to venture capital is also a helpful reminder that venture capital is not considered by allocators to be sui generis. Instead, venture capital sits within a broader asset allocation matrix of our customers, where VC is unlikely to be little more than an afterthought. It’s a curiosity. It’s not the main character.

If the power law is universal, does the VC industry have any unique defining features?

Illiquidity as the differentiator

Venture capital is an illiquid asset class. A small percentage of VC-backed companies exit via M&A each year, and even fewer exit via the desired IPO route (only 935 IPOs from VC-backed US companies since 2010). Figure 2 shows that annual distributions represent c.15% of NAV in any given year.

Figure 2. Average US VC fund distributions as a share of beginning NAV

We are going to argue that the illiquidity of VC is its unique defining characteristic, and is the right prism through which allocators should look at the asset class. It is precisely because VC is illiquid (meaning long holding periods in growth companies with ultimate capital returns) that it is so attractive.

Huh? How does that work?

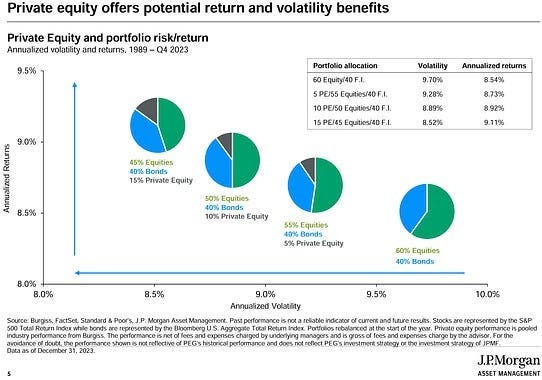

Allocators who have moved beyond the traditional 60/40 equities/bonds allocation model have seen that higher allocations to private markets have led to both higher returns and lower volatility. This is dream land for those searching for the efficient frontier. In JP Morgan’s data from 1989 to 2023, the more alternatives included, the higher returns and lower volatility in the portfolio (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Different portfolio allocations and their respective returns relative to volatility.

How is it that alternatives deliver superior returns & lower volatility?

VC (& private equity) benefit enormously from long holding periods because:

Returns compound over time. Without the option for selling / rebalancing, the best performing assets continue to compound in value over time. $1bn+ outcomes are not created overnight. Managers cannot be tempted to sell their positions because there is no well established exit mechanism. We do not experience the over-trading seen in public markets. Managers instead should use time to ensure that existing investments perform even better (you know, by adding value in the way promised to LPs).

There is more (perceived) valuation stability in private markets than in public markets. Quarterly / monthly valuations set by committees are preferred to the brutality of the public market every day. Cliff Asness, co-founder of AQR, likes to describe this phenomenon as “volatility laundering” where the risk-return profile might not fully reflect the underlying volatility. In any event, this valuation stability is appreciated by asset allocators, especially when there is more volatility in their public portfolios. In the short term, GPs & LPs alike look good with TVPI appreciation.

Delayed liquidity promotes longer term thinking about relationships between GPs and LPs. This is very aligned with LPs’ long-term mindset for their ultimate investors; GPs find it invaluable to have LPs who can support them across multiple funds. With no carry for 10+ years, GPs & LPs must be considering a 15+ year relationship across multiple funds. This allows for capital stability.

We have made the case here that enforced holding periods compounds growth which actually creates benefits for VCs and their LPs.

OK, so why are folks so up-in-arms about illiquidity?

Unpredictable liquidity is the issue, not illiquidity itself

Many VCs are currently very exercised on X around the idea that an extinction event is coming for emerging managers because illiquidity in VC means less capital is available to LPs to recycle into the next vintages of VC in general and into emerging managers in particular. The 30-50% decline in VCs may come to pass.

But one could argue that it was actually the excess of liquidity in 2020/21 that has created the problems, not the current lack of liquidity. Bill Gurley has famously described VC liquidity as being saw-toothed – grows slowly, then scales to a peak, then contracts immediately. This shape of liquidity (Figure 4) is problematic, not the illiquidity itself. Above all, allocators just want predictability.

Figure 4. US VC exit activity

The biggest problem created by high liquidity in the ZIRP era ($797bn of VC exits in 2021) is that it pulled forward fund cycles. Huge waves of capital needed a home, leading to GPs to dream up ever more elaborate investment strategies to unlock LP capital. 3 year fund cycles contracted to 12-18 months. Strategy drift became pervasive. The memes of VCs moving from SaaS to FinTech to web 3 to AI to deep tech are fair.

By pulling forward deployment in 2021 & 2022, there is less capital available in 2024 (& beyond) for new funds. Hence all the stories about the 30-50% extinction events for emerging managers.

In addition, the storied “Tier 1” brands became capital accumulators, seeking to raise ever larger funds, just because they could. The combined recent $16bn fundraise of A16Z ($7.2bn), General Catalyst ($6bn) and Khosla Ventures ($3bn) equals almost exactly all VC capital raised by emerging managers in the US in 2023. (This is no criticism of A16Z – play the game as you see it).

LPs share some of the blame here. The industry would have done itself a favor by re-reading the Kauffman report’s excellent 2012 report, “We Have Met The Enemy… and He Is Us.” It is a seminal critique of venture capital from an LP’s perspective, highlighting underperformance relative to public markets, low capital returns from realized exits, the short-term nature of the sector and the fundamental misalignment of interests between GPs and LPs. Sound familiar?

The second problem created by excess liquidity is that most of the companies that went public during the ZIRP era were not of the highest of quality. They should have remained private for longer. This hit LPs directly if they were locked up at IPO. It also hit their public market managers’ books. More importantly, it destroyed trust in the public markets about the quality of VC-backed companies. The bar for taking companies public is higher today. This will extend the fallow period of liquidity, with continued knock-on effects for VC fundraising.

To reiterate, LPs appreciate that venture has long holding periods, but ultimately they need capital returned and they dislike the unpredictability / cyclicality of liquidity events. What if you could smooth out liquidity? What if liquidity became predictable?

Secondaries as a strategy

A sophisticated secondaries market could be one way to allow for predictable liquidity for LPs.

Secondaries (selling primary interests in VC companies and VC funds) used to be a dirty word in VC. Given the lore of riding a unicorn to its ultimate IPO, it was seen as risk averse (potentially even not founder friendly) to be seen to sell before a liquidity event.

Not so anymore. With unpredictable liquidity in IPOs & M&A, secondaries have become more mainstream. Secondary marketplaces & funds are popping up with some frequency (with a helpful list of funds here). In a 2022 report, Industry Ventures estimated that there would be $138bn of VC secondaries in 2023.

It is still fairly early in the development of secondaries markets. There are a number of major issues to be ironed out:

Companies don’t really want trading in their cap tables. They understandably want to control who owns their equity. With some frequency (c.15% of the time by Forge’s calculation), companies are blocking unauthorized secondary sales via ROFRs. This creates a level of distrust of the validity of proposed trades in the secondary market. We believe that an issuer-led model (like NASDAQ’s private market) is probably the right way forward.

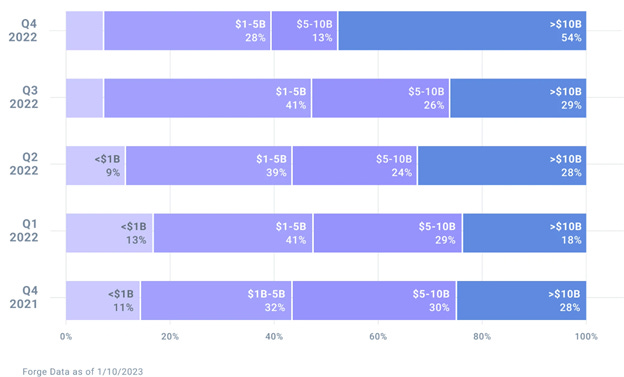

Secondaries are really only available to $1bn+ companies. Forge Global has data (Figure 5) to show that c.90% of activity on their marketplace is for famed names with values of above $1bn (and c.30% is for companies worth $10bn+). Secondary liquidity is currently not available for smaller companies.

The cyclicality of capital markets and the current low levels of liquidity means that the bid/ask spread for positions can swing wildly (Figure 6), ensuring that there is no real consistency of a “market.”

We anticipate that the secondary market could iron out these issues over time as VC continues to develop from a cottage industry to an institutionalized asset class. But it will take time.

Figure 5. Forge Global markets volume by company size (% of total dollar volume)

Figure 6. Forge Global distribution of trade premium/discounts to last primary funding rounds

Listing an index as liquidity

At SignalRank, we believe that an even more robust model for ensuring predictable liquidity for LPs is for the index itself to be listed. A public listing would enable investors to convert MOIC into DPI at their option.

The concept of a listed entity for private investments could have the benefits of illiquidity described above for the underlying assets (compounding returns & stable valuations), while also allowing investors predictability in managing their cashflows.

If this model were adopted by the private markets at large, it is likely that many of the benefits of being an illiquid asset class would disappear. Returns would be much more in-line with other public market assets. But, in the meantime, this potentially represents an arbitrage opportunity for investors seeking the compounding growth of private assets with the reliable liquidity of the public markets.

We are not alone in this thinking. KKR recently published a whitepaper that suggested that allocating to evergreen structures alongside traditional 2/20 funds can improve returns.

Concluding thoughts

The long holding periods for venture capital assets has allowed the industry to deliver superior top quartile IRRs which are what make it so attractive to LPs. The challenge for the industry is that this illiquidity is too unpredictable.

At SignalRank, we believe that a publicly-listed vehicle can provide the best of both worlds, by focusing on deploying into power law compounding companies while simultaneously enabling investors to generate liquidity as required.