This week Bain released their annual global private equity report. As private equity ($5 trillion global AUM) is the big brother to venture capital ($2 trillion global AUM), trends in private equity tend to follow in venture capital thereafter.

The report comes at a time of change for the private markets industry (including both PE and VC).

The growth of the private capital market has been rapid over recent decades. According to Preqin, the private capital market has grown from $716 billion in total AUM in 2000 to $15 trillion as 2023. The major twin growth engines in recent years have been low interest rates and multiple expansion.

Yet the key growth levers for the industry are shifting.

This post will summarize these changes highlighted in the Bain report and seek to infer what may be coming down the tracks in the venture industry.

In particular, we are going to pick out three trends in private equity (which throughout this post is really shorthand for buyouts) that are now starting to impact VC:

Capital flight to quality managers

Rise of alternative liquidity strategies

Public listing of GPs

We will then look at key disruptions that Bain anticipates PE shops will have to grapple with in the coming decade, and how they might impact VC in the future.

Current trends impacting private equity

1. Flight to quality

Bain notes how fundraising across private asset classes (including PE & VC) fell for the third year in a row, ending 2024 at $1.1 trillion, down 24% year over year and 40% off the all-time peak of $1.8 trillion in 2021. The number of funds closed dropped 28% to 3,000, which is about half the annual pace the industry was keeping before Covid.

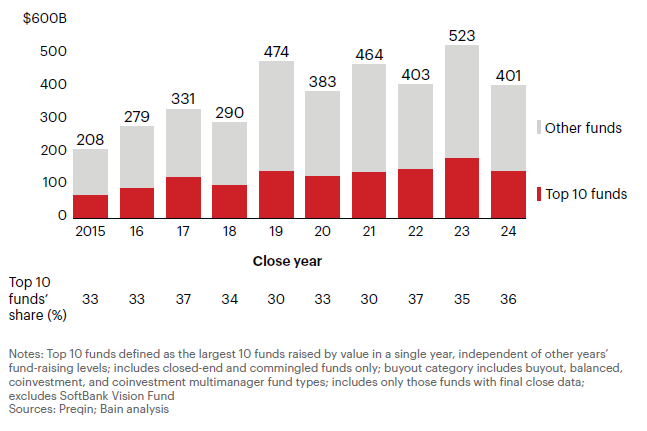

In both private equity and venture capital, LP capital is funneled to the largest, most experienced funds. In private equity, the top 10 funds in capital raised captured 36% of the pie in 2024 (Figure 1). In fact, experienced managers absorbed all capital (98%, with just 2% for emerging managers), and 40% went to funds raising $5 billion or more.

Figure 1. Global buyout capital raised (2015-24, $bn)

According to Bain, investors are “increasingly looking for the safe haven of large, experienced funds, especially those that offer a value proposition that stands out from the crowd.” The winners have been firms at scale with the resources and capabilities to win across multiple asset classes (e.g., Blackstone, CVC, KKR, Apollo, and TPG). In addition, firms with “a clear focus, expertise, or capability set that enables them to consistently generate alpha (tech specialists like Thoma Bravo and Vista, for instance)” have done well.

Scale has additional benefits, from supporting sophisticated back-office functions (accounting, tax, HR) to having more resources to building investment capabilities. Larger funds can also can invest more in the data and analytics capabilities that are becoming increasingly valuable in underwriting and gaining differentiated insights.

A very similar trend is taking place in venture capital, where Pitchbook illuminates how nine funds took $35bn of capital last year, half of the total raised. Andreessen Horowitz raised 11% of all VC capital last year.

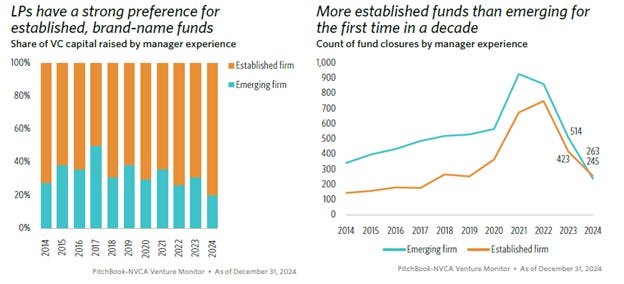

The Q4 2024 NVCA Pitchbook Venture Monitor makes for sober reading for emerging managers. ~20% of VC capital is now going to emerging managers, and more established firms than emerging firms closed funds for the first time in a decade (Figure 2).

Figure 2. VC fundraising for emerging vs established firms

2. Alternative liquidity strategies

Distributions are not keeping pace with the growth of the private equity industry. While global buyout AUM has tripled over the past decade, distributions as a percentage of NAV have fallen from an average of 29% from 2014 to 2017 to 11% today (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Global buyout distributions as a % of net asset value

Pressure on GPs to return capital to LPs is reaching a crescendo. As a result, new liquidity mechanisms are emerging to solve this problem, such as minority stakes, secondaries (especially continuation funds), NAV loans, and dividend recaps. These enable GPs to return cash while holding on to an asset for longer. While not a replacement for exits, these mechanisms helped improve cashflow in the industry.

Stepstone’s data demonstrates how GPs are deploying a full range of tools to generate liquidity (Figure 4). From 2014 to 2016, the fully realized portion of total portfolio company realizations averaged around 44%. But the 2019 vintage has been impacted by the exit downturn, leading to partial realizations accounting for 65% of total realizations (vs 37% for 2014).

Figure 4. Assets partially or fully realized at holding period of 5 years

The growth of the secondaries market has been most notable, now reaching $601bn in secondaries AUM (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Global PE secondary assets under management

The venture market is experiencing similar liquidity constraints, which itself is impacting the ability of venture funds to attract more LP capital. The NVCA Pitchbook Venture Monitor report shows how VC distributions as a % of NAV is now as low as 6.5% in 2024 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. VC distributions as a share of net asset value

In a similar fashion to the private equity market (albeit at a more nascent stage than in private equity), venture-backed secondaries have experienced significant growth as a result. Industry Ventures estimates here that the venture secondary market is now $130bn per year (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Global TAM for VC secondary transactions

New secondary funds include a $1.45bn fund for Industry Ventures and a $3.3bn fund for StepStone. In addition, multi-stage funds (like Lightspeed) are registering as Registered Investment Advisers which will allow them to deploy more than 20% of funds as secondaries bets.

3. Public listing of GPs

The Bain report does not cover the historic trend of private equity GPs deciding to list. This may be because this is old news: Blackstone went public in 2007, KKR in 2009, Apollo in 2011, Carlyle in 2012, Ares in 2014, Blue Owl in 2021 and TPG in 2022.

Yet this is another good example of a trend that has impacted private equity and is starting to emerge within VC land. In particular, Axios broke a story this week about General Catalyst exploring options to go public (with Andreessen Horowitz also rumored to be considering this path). Cue lots of reactions on X about the irony of private asset managers seeking to go public, leaks of GC’s returns and pointing out echoes with the Goldman Sachs’ 1999 IPO whose stated goal in going public was to raise “permanent capital to grow”.

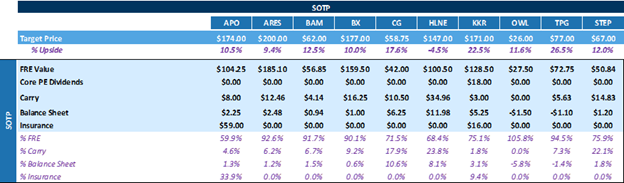

The trend towards public listing supports the narrative that multi-stage VC GPs have become asset accumulators more focused on management fees than carry. Indeed, fee related earnings (FRE) is the key measure on which listed alternative managers are valued. In Goldman Sachs’ recent report on listed alternative managers (“Valuation fatigue drives recent underperformance”, 19 February 2025), their Sum Of The Parts valuations in Figure 8 show that the overwhelming majority of value is based on FRE, not carry: “we continue to see organic management fees as the most important indicator of forward growth trajectories.”

Figure 8. Listed alternative asset managers SOTP valuations

Turning to the future

The three trends detailed above are well underway within private equity, and now starting to impact venture capital. We will now turn to future trends anticipated by Bain in the next decade, especially: margin compression, the evolution of sources of LP capital and asset manager M&A.

1. Margin compression

The 2/20 fee structure has been the standard model within private equity. Increasing competition for capital has led to quiet fee concessions, as well as the growing expectation from LPs for fee free / free lite co-investment opportunities. Bain believes that average net management fees have been reduced by “as much as half since the Global Financial Crisis.”

In addition, the convergence of private and public markets is adding to the pressure. Established low fee public market asset managers, such as Vanguard & Franklin Templeton, are establishing alternative investment products for their clients who seek diversification from the public markets.

Bain argues that convergence between the public and private markets “raises the prospect of something entirely new for private capital: the proliferation of very large firms that charge lower fees for simply tracking the market (beta) vs. trying to beat it (alpha).”

2. New LP sources & structures

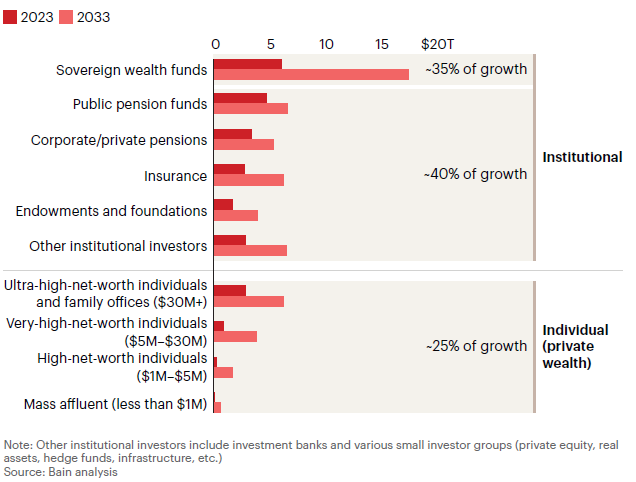

Endowments and large institutions have historically been the mainstay of private market funds. Private wealth and sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are new pools of capital in the private market that Bain expects will account for approximately 60% of growth in alternative AUM over the next decade (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Global alternatives AUM

Today, individual investors hold 50% of global capital, but represent 16% of AUM in alternative investment funds.

With an influx of retail capital, we should anticipate novel structures so that products can be sold on the shelves of channel partners like private banks, wirehouses, and registered investment advisers: “real estate and private credit funds have led the charge with retail-oriented products, but private equity is catching up fast with semiliquid products that have lower minimums and are aimed at investors who need more liquidity than institutional investors”. In 2024, Blackstone alone saw $23 billion flow into its set of semiliquid products aimed at retail investors. In the same report noted above, Goldman Sachs demonstrates how retail-related management fees grew 34% YoY on average for listed alternative managers.

Likewise, SWFs are transforming private capital’s supply side. State-based institutions ADIA in Abu Dhabi and GIC in Singapore have each grown their exposure to alternatives by more than 10% annually over the past decade and have seen their alternatives programs grow to around $360 billion and $250 billion, respectively. Bain notes that “as these giants grow in sophistication and build new capabilities, they are becoming much more than the passive investors of the past. This will present threats and opportunities across the alternatives landscape that every fund will need to think through.”

3. Strategic M&A

M&A has historically not been a key driver in private equity. Organic growth has been strong, while firms lacked the balance sheet to finance acquisition and integration complexity from private partnership structures has put folks off consolidation.

This appears to be changing, and fast. Bain notes that M&A has accelerated meaningfully in recent years (citing EQT’s BPEA deal and BlackRock’s acquisition of HPS & Global Infrastructure Partners; Figure 10).

Figure 10. # of strategic acquisitions of alternative asset managers

Within VC, General Catalyst has been active in expanding their capabilities via M&A, most notably through the 2023 merger with La Famiglia (a German seed fund which expands GC’s European presence) and the 2023 acquisition of Venture Highway in India.

Therefore what?

With the caveats that VC tends to be more cyclical than PE and that VC is more quickly influenced by technology supercycles, we have seen here how venture capital and private equity are impacted by similar industry trends. Changes within private equity tend to be a leading indicator for what might happen in venture capital.

If we turn to SignalRank specifically, we feel these ever stronger industry tailwinds at our back. The immediate catalyst was BlackRock’s acquisition of Preqin to signal the importance of data in indexing the private markets. Yet Bain’s report here suggests that our strategy of establishing a low cost, publicly traded, smart beta VC vehicle is firmly in-line with the direction of travel for the broader industry.