OK, so this headline may be a little hyperbolic. But it is an interesting thought experiment to consider a world where there are effectively no IPOs. You know, like the world we have been living through since 2022.

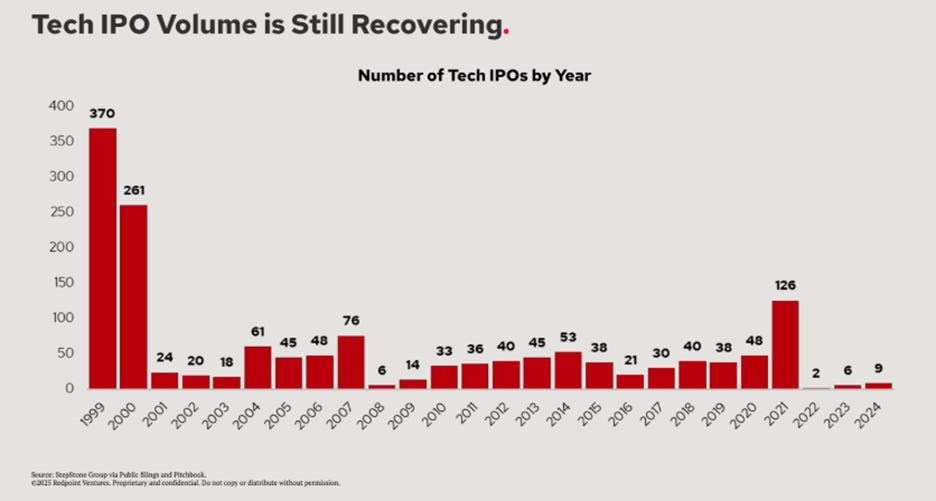

Redpoint’s Logan Bartlett recently published this excellent state of the VC market deck, including a slide on IPOs which he optimistically characterized as “still recovering” (Figure 1). There have been fewer than 10 tech IPOs in each of the last three years, much fewer than even at the nadir of the dot com era.

Figure 1. Redpoint’s view on the state of the IPO market

Similarly, the NVCA Pitchbook Venture Monitor report shows how VC distributions as a % of NAV were as low as 6.5% in 2024 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. VC distributions as a share of net asset value

These charts reflect the state of play as at the end of 2024. Hope springs eternal that more companies go public in 2025 and 2026. This would lead to a healthy recycling of capital back into the ecosystem.

CoreWeave went out last week (albeit raising only $1.5bn of their target $4bn). Mooted upcoming IPO candidates include Klarna, Chime, Figma & Discord.

But notably not SpaceX (founded in 2002), or Stripe (2010), or OpenAI (2015).

It feels like the slowdown in IPOs is not simply a case of reversion to the mean; there are some structural changes that are impacting companies’ desire to go public.

Citing CoreWeave’s underwhelming IPO, the FT talks about “IPO enshittification, where the public markets are offered the runt of the litter.”

So why are these iconic companies choosing not to go public? And if this trend of indefinitely delaying a public listing continues, what could alternative liquidity mechanisms look like?

Why are companies staying private longer?

An IPO is a major milestone for a company, with the potential to bring capital, liquidity, transparency & prestige. But the draw of a public listing appears to be less compelling than it used to be.

The median age of a company at its IPO has increased from six years in 1980 to eleven years in 2021. At the same time, the number of US public companies has been shrinking, from a peak of ~7,300 in 1996 to ~4,300 today.

This longer gestation period as a private company has created a new category of late stage businesses which Altimeter’s Brad Gerstner has dubbed as “quasi public” companies (such as Databricks or Epic Games). Matt Levine similarly calls these “private-is-the-new-public” companies.

This is a recognition that the recent trend is for companies to stay private for at least the first $20bn of value (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Proportion of first $20bn in value captured as or IPO (%)

There are several dynamics at play here, including:

Market sentiment: the public market has been a whipsaw ride of late, increasingly so since Covid. Companies want stable pricing dynamics & environments. Recent geopolitical instability has hardly helped.

Poor IPO performance: VCs foisted a very poor set of companies onto the public markets during ZIRP. The Renaissance IPO ETF demonstrates how IPOs have underperformed the S&P 500. The bar for going public is now much higher.

More developed private capital markets: there is more capital available in the private markets, both on the primary & secondary side, including for founders & employees.

Weaker VC governance: a competitive VC market has led to the development of ever more “founder friendly” terms and approaches in VC. Larger funds (requiring more capital to be deployed into more companies) and faster musical chairs by GPs across funds further weakens the bond between founders & VCs. Today’s VCs do not appear to be holding founders’ feet to the fire to go public.

Longer-term mentality: Paul Graham’s post on “founder mode” was recognition that founder-led companies outperform. Founders tend to have a longer-term mentality which is not always appreciated by short-term investors focused on quarterly earnings. Add on top of that the regulatory burden on founders of running a publicly listed company.

Better still is to hear these themes first-hand from generational founders; the Collison brothers, founders of Stripe, eloquently summarize the case against going public here. You can almost hear the gnashing of teeth by Benchmark’s Bill Gurley, a vocal advocate for companies going public early.

Stripe and a handful of these high quality large private companies could go public if they chose to do so. The elephant (or zombie unicorn) in the room is the companies which raised too much money during ZIRP and are now stuck. From the deck above, Logan Bartlett shows how 72% of 2021 unicorns have not raised an up round in the last three years, left in “Zombieland”. They can’t go public, they’re not growing and they’re not profitable. They are a major blockage in the venture ecosystem, trapping capital and putting off LPs from future allocations.

If the FT is right (in the above article) that IPOs are now for the “desperate and distressed” who have no other choice, the irony may be that the IPO is the perfect solution for zombie unicorns?

What to do?

The short term picture is not pretty. If IPO levels remain depressed, the natural recycling of capital will continue to be affected. And this post assumes generational companies want to stay independent; we are going to ignore M&A even though M&A accounts for the majority of exits by number & value (where the hope is that Google’s $32bn acquisition of Wiz is approved, acting as a catalyst to further exit activity).

None of the ideas presented here (secondaries, continuation vehicles, tokenization and liquid investment structures) are even remotely of the scale required today. But potentially these additional liquidity avenues can add to the return of capital and support the venture ecosystem.

1. Secondaries

Secondaries enable companies to stay private longer while providing long-time investors and employees liquidity.

Venture-backed secondaries are experiencing significant growth. Industry Ventures estimates here that the venture secondary market is now $138bn per year (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Global TAM for VC secondary transactions

New secondary funds include a $1.45bn fund for Industry Ventures and a $3.3bn fund for StepStone. Multi-stage funds (like Lightspeed) are also registering as Registered Investment Advisers which will allow them to deploy more than 20% of funds as secondaries bets.

In addition to the advent of new secondary funds, platforms like Zanbato are bringing new buyers, streamlining the transaction process and enabling greater transparency on pricing. This is also happening for employee stock with platforms such as EquityZen & Secfi.

It is still early in the development of secondaries markets. Some major issues still need to be ironed out:

Companies don’t all want trading in their cap tables: They understandably want to control who owns their equity. With some frequency (c.15% of the time by Forge’s calculation), companies are blocking unauthorized secondary sales via ROFRs. One trend that is giving companies more control is company-run tender offers for early stage investors & employees.

Secondaries are really only available to $1bn+ companies: According to Forge Global, c.90% of activity on their marketplace is for famed names with values of above $1bn (and c.30% is for companies worth $10bn+). Secondary liquidity is currently not available for smaller companies.

Cyclicality: the cyclicality of capital markets and the current low levels of liquidity means that the bid/ask spread for positions can swing wildly, ensuring that there is no real consistency of a “market.”

More broadly, the secondary market is still too small. Industry Ventures’ chart above estimated $53bn for direct secondaries for 2023. This is but a drop in the VC ocean, representing 2% of $2.9 trillion of unicorn valuations. Pitchbook argues here that secondaries are “realistically too small to materially impact the asset class. Even in 2024’s muted environment, secondaries could provide only 40% of the $149 billion exit value, assuming the entire available secondary market is sold”.

2. Continuation vehicles

Continuation vehicles enable existing LPs to exit old assets to new buyers or to move these assets into a new fund. This can also reduce pressure on founders being asked to provide liquidity at the company level.

These vehicles have attracted lots of noise but not much action (apart from Insight Partners’ recent $1.3bn second continuation fund). The issue is the disconnect in value expectations between GPs and LPs; the requested discounts are much higher than most VCs can stomach. For example, Shasta Ventures’ LPs voted against the GP’s attempt to set up a continuation vehicle in 2024, due to a proposed 35% discount from the 2023 values.

Continuation are unlikely to be anything other than a niche product.

3. Tokenization

The “tokenization” of real world assets to allow illiquid assets like real estate or art to be fractionalized and traded on digital platforms could be another solution for private companies seeking liquidity.

Robinhood is pushing this idea as a way to expand retail access to alternative assets. They argue that the problem is that tokenization is restricted to “accredited investors”, thereby blocking most retail investors from this market. They would like to see a new regulatory model to accelerate tokenization (and broader access to alternatives).

Again, BlackRock’s Larry Fink wrote in his annual Chairman’s letter that he expects “tokenized funds will become as familiar to investors as ETFs” (assuming we can solve identity verification).

As of today, tokenization is a nice idea with little in the way of meaningful traction. One to watch.

4. Liquid investment structures

We are seeing more novel investment structures for alternatives, especially as the LP base broadens to include more retail investors. Some of the benefits of these structures include greater liquidity for investors. As such, investors could secure liquidity even if the underlying assets remain private.

A cynical take could be that the lack of liquidity in alternatives has forced GPs to expand their LP base beyond traditional pools of capital, if GPs want to continue to scale their AUM. It is also true that retail is underweight alternatives relative to endowments / institutions (where retail represents 50% of all AUM but only 16% of alternatives capital).

Retail investors (and retail regulatory regimes) require greater access to liquidity. Hence “innovation” such as the Apollo semiliquid private credit ETF, enabling retail to invest into private credit models managed by some of the best managers in the world.

An alternative approach is for the GP themselves to list, which is what General Catalyst is rumored to be exploring (and what large PE shops have already done).

SignalRank itself intends to pursue a listing to enable our investors to convert MOIC into DPI at will, thereby providing liquidity on demand while simultaneously allowing the underlying companies to remain private.

Some concluding thoughts

There are reasons for optimism in the IPO market, with a healthy pipeline of opportunities for the next few quarters. Nevertheless, the development of alternative liquidity options reflects a more sophisticated and mature market. It will just take time for some of these models to achieve any meaningful scale.