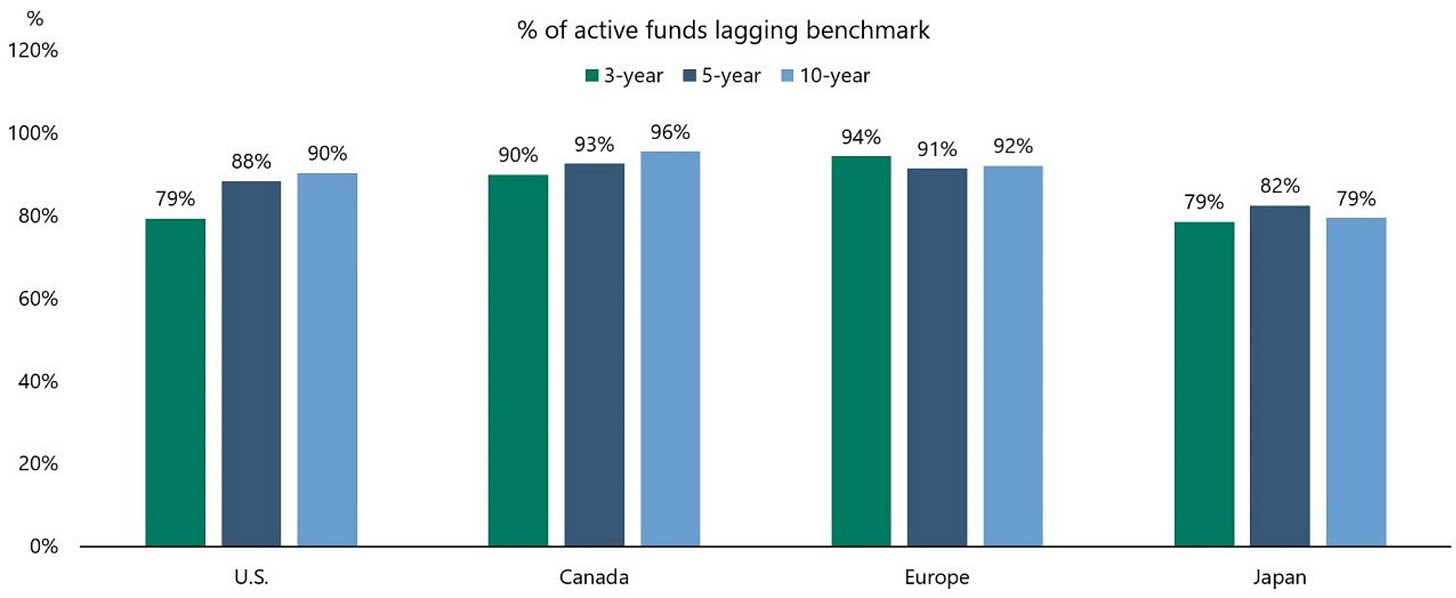

90% of active managers lag the US public market benchmark over 10 years, according to this recent chart by Apollo (Figure 1). If an index beats most active managers in the public market, shouldn’t the same logic apply to the private markets?

Figure 1. Active public funds have lagged their respective benchmarks

Source: Apollo

The challenge is to agree on what an “index” constitutes given the inability to fund every round in the market. At SignalRank, our answer to this question is to argue that 30 investments a year is a statistically representative sample of the top 5% of Series Bs selected by our model.

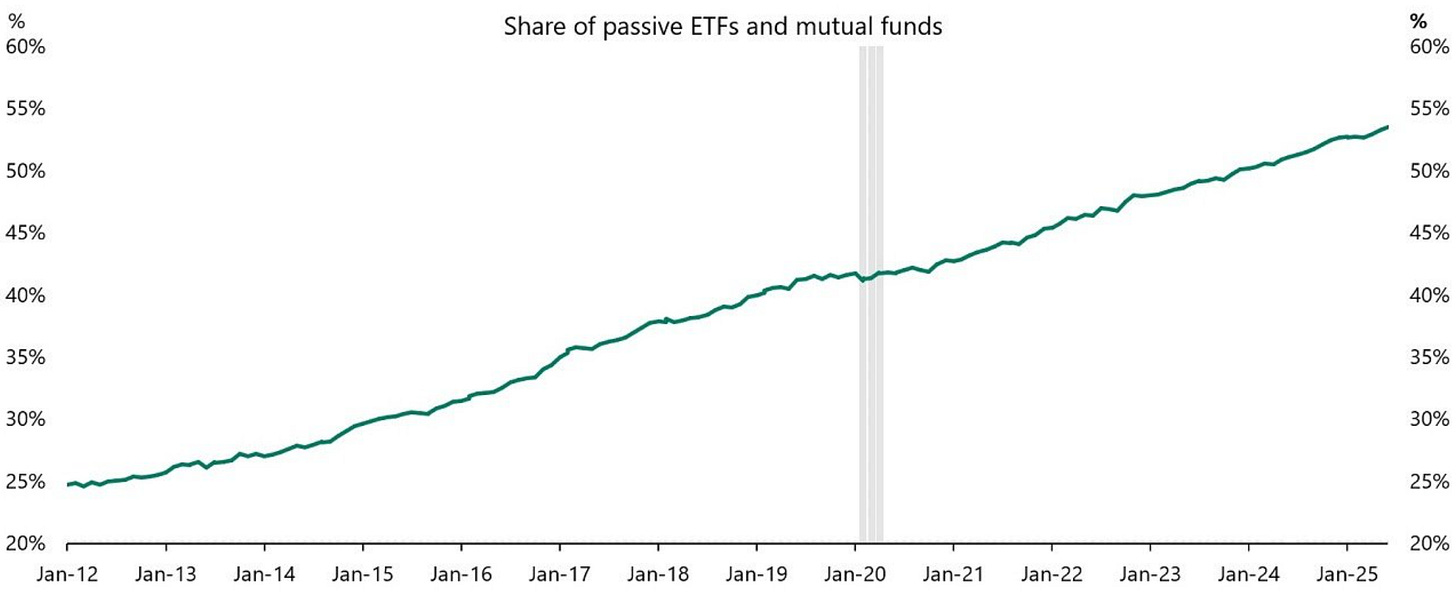

While the majority of ETFs and mutual funds are now in passive vehicles, it remains early days in the creation of passive private structures. As such, the Great Man / Woman theory remains dominant. Equidam’s Dan Gray published a piece today on how VC LPs back “confidence over competence”.

This is the private market equivalent of what John McQuown, father of passive investing, explained in relation to public markets:

“the vacuousness of the traditional methods of portfolio management, which, were little more than ‘ . . . a variation of the Great Man theory. A Great Man picks stocks that go up. You keep him until his picks don’t work any more and you search for another Great Man. The whole thing is a chance-driven process. It’s not systematic and there is lots we still don’t know about it and that needs study.’”

Correlation Ventures previously argued that the value of a venture capital firm is little more than the value of the individual GPs. When a partner moves from one venture firm to either a worse or better performing one, the performance of that partners’ investments remain largely the same. In fact, persistence in performance by partners is six times more important at explaining fund returns than firm attributes.

Yet we still subscribe to the argument that the core product that VCs are selling is their (collective) decision-making engines, not the individual decision-making of a sole GP. Indeed, Correlation’s own analysis showed that individual partner signal only explained 12% of all returns (with 86% of returns explained by other factors).

Indeed, our core investment data model at SignalRank is based at the firm level, not the individual. This is for various reasons:

The data is better at the firm level than the individual level, and we want to compare apples to apples. Not all firms attribute deals to individuals.

No one individual scores high enough to drive investment decision on our model

Investment decisions are usually taken by committees, not individuals (even if sourced / led by individuals)

Having said that, some individuals do deliver stellar performance. One name that consistently comes up in conversations as a high Series B performer is a16z’s Martin Casado.

In this post, we consider Martin Casado’s performance as an illustration of what exceptional GP performance looks like – and why the Great GP theory remains seductive.

A caveat is that this analysis is based on publicly available Crunchbase data which we know does not show the full picture (especially as we are investors in two Martin Casado Series Bs which have not yet been announced). But it is directionally illustrative.

Martin Casado’s performance

Martin Casado is a GP at a16z, focused on AI, data & analytics. He is a seed to Series D investor, primarily focused on Series A & Series Bs.

On our internal GP ranking system, he has consistently ranked as a top 10 GP over the last five years (and ranked #1 last year).

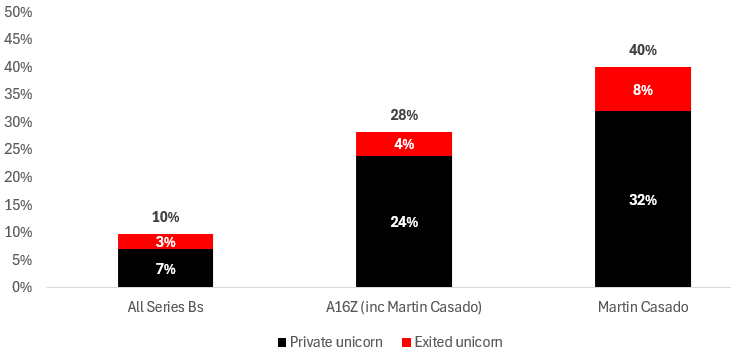

Since 2015, our data shows he has invested in 25 Series Bs, of which an astonishing 40% have gone on to become unicorns (Figure 2). 64% of his Series Bs went on to raise a Series C (compared to 33% for the market average).

Figure 2. Unicorn hit rate for Series B investments, 2015-25

Source: Crunchbase

This unicorn hit rate is not because he is paying higher prices at Series B to create unicorns at Series B. The average Series B he participates in is $34m (with a median of $30m).

This Series B performance is really derivative of his Series A investing, given that 68% of his Series B investments were follow-ons from his Series A investments.

In fact, his Series A investing is perhaps more remarkable still in that 25% of his Series As have gone on to become unicorns (compared to 3% for the market average).

Before we get too far into hagiographic territory, it is worth pointing out that Casado on his own represents 10% of all a16z Series Bs and 14% of all a16z Series B unicorns. Andreessen Horowitz is called Andreessen Horowitz for a reason; the firm’s two founders are active investors and have led the firm since inception. LPs are buying the Andreessen Horowitz funds, not the Martin Casado funds.

Instead, Casado’s results should perhaps be seen within the context of the a16z machine, where he is empowered by a16z’s brand, platform, capital and decision-making engine.

Casado could of course spin out as a solo GP. But, as in the music industry, there is risk that not every solo career eclipses the former success of the band.

Some concluding thoughts

The argument for passive structures in the public markets has been won, with the majority of ETFs and mutual funds now in passive models (Figure 3). The equivalent percentage for private markets is probably <1% today.

Figure 3. % of ETFs and mutual funds in passive vehicles

Source: Apollo

Martin Casado’s track record shows why the Great Man/Woman theory endures in the private markets: exceptional individual talent can produce extraordinary results. But we would argue that his success is somewhat inseparable from the structure of a16z.

And a16z may well be in the 10% of active funds that outperform the industry benchmarks over 10 years (in part because the engine includes great GPs like Casado). But for most VC allocators who cannot investing directly in a16z, we expect the Great GP theory to give way to more systematic approaches (just as has happened in public markets).