Q3 VC funding data is in. There were 1,175 announced seed rounds globally in Q3 2024, down 25% compared to Q3 2023 (or down 48% compared to 2021). Similar patterns were seen at Series A, Series B & Series C (all down c.15% vs Q3 2023).

The data suggests VC is in flux. The venture capital industry is currently holding its breath. Waiting for the excesses of the ZIRP bubble work their way through the system. Waiting for the outcome of the US election. Waiting for exits.

But, more than anything else, the venture capital industry is looking for the next grand narrative. The great hope is AI. AI will wipe away the sins of the 2020/21 bubble and bring back the feelgood factor in the industry.

Here’s a characteristically understated slide from a recent SoftBank presentation (unclear whether or not this is to scale):

Figure 1. SoftBank’s Evolution of Humanity

There is consensus (always dangerous) that AI is the next big technology platform. The big question is around timing. The capital deployed into AI and the rapid adoption rate of products is already eye-watering. But enterprise rollouts of AI solutions remain at the experimental phase. And best not to mention the current unit economics of running foundational models. In other words, it is early in the AI era.

VCs have tried their best to look relevant with the arrival of this new platform technology. It’s just that the first phases of the AI cycle have not favored VCs & startups. Not yet.

Even the VCs who have benefited thus far from the AI boom (e.g. Khosla Ventures) have had to pull some fairly unnatural maneuvers. See the funky 100x capped structure of the OpenAI investment, as well as the existence of OpenAI’s unusual non-profit entity. Or the apparent round-tripping between Cerebras & G42. The Economist talks about how “generative AI is bringing disruption to the home of America’s disrupters-in-chief. Enjoy the Schadenfreude.”

With AI, we have been in the early part of the platform cycle that requires huge capex investments by the hyperscalers to build the foundational infrastructure layers (data centers, hardware & core algorithms), on top of which next gen VC-backed software can be built. VC is rocket fuel which *in general* (don’t @ us with names of successful hardware exits) is better suited to high margin & scalable software (because software can be a more capital efficient play to deliver the largest power law returns required to make the whole thing make sense).

VC was not the appropriate financial instrument for the initial phase of the AI game. The VC industry’s pockets are not deep enough to play in the foundational layer. A $100m Series B looks cute next to a $100bn foundational model.

Beyond seed & Series A, AI’s capital requirements and its epic valuations are pricing out almost all VCs at growth stages. This week even saw two funds “give back” later stage capital to focus instead on earlier stage opportunities. CRV decided not to deploy $275m from its $500m opportunity fund. PeakXV trimmed its 2022 fund by $465m for similar reasons.

This is a movie we have seen before. Aileen Lee wrote a piece last week about how it takes time for the startup winners to displace the incumbents in every technology cycle. Maggie Basta echoed this here by looking exclusively at infrastructure software companies in each cycle (including AI). We agree. It’s early.

We want to take a slightly different approach to make the same point, by looking through the lens of the layers for each cycle in previous platform shifts, like the rise of the internet, cloud computing & mobile. Each of these shifts went through a similar trajectory: heavy capital expenditure investments at the infrastructure & hardware level, followed by a wave of middleware & application software that capitalized on the newly available technology. AI is currently at a similar inflection point.

This is one possible explanation for the slowdown in funding in Q3. VCs understood these dynamics from previous cycles. And have been waiting.

Let’s revisit some history.

VC slowdown in context

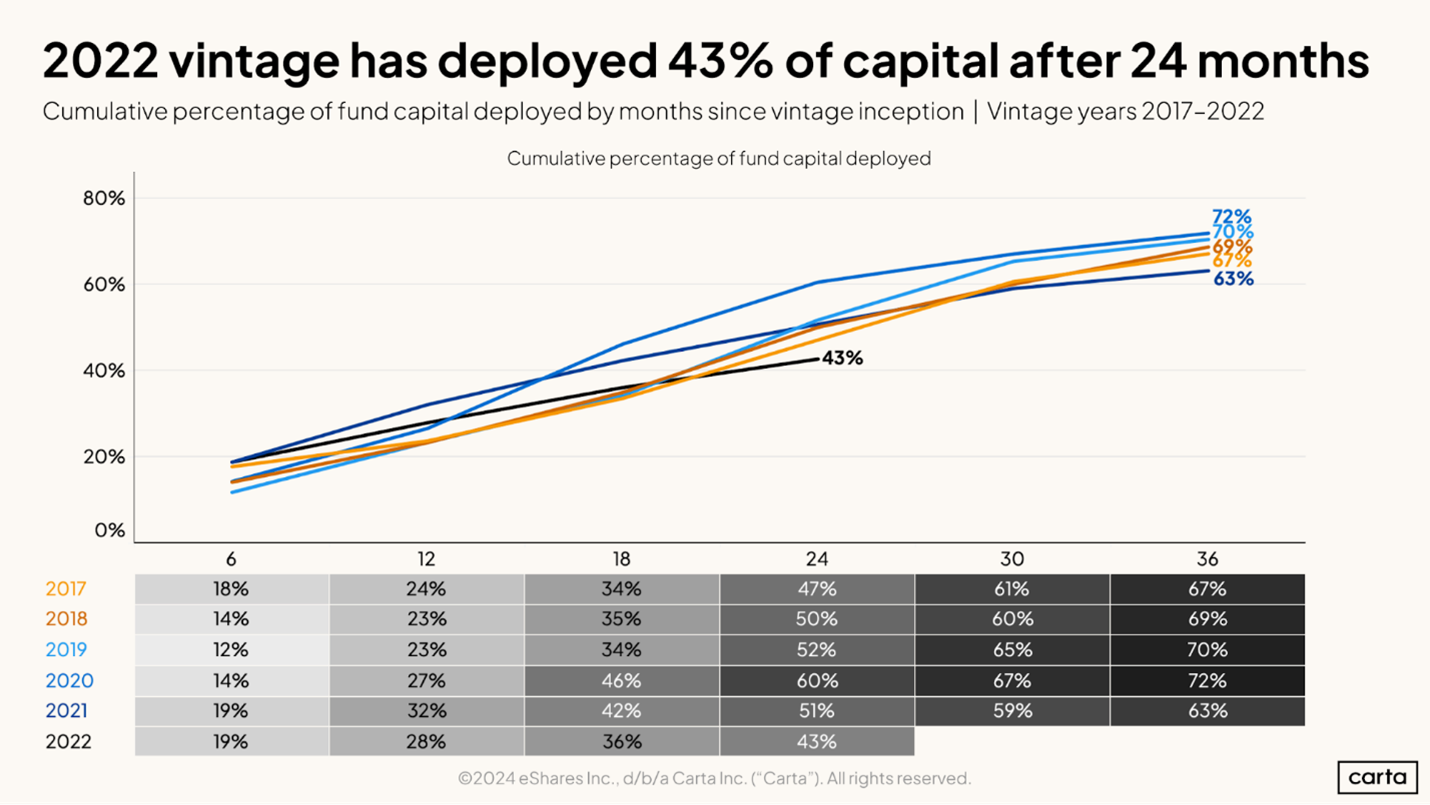

Capital deployment in venture capital has slowed substantially since 2021. Carta has shown how the 2022 vintage has only seen 43% deployed after 24 months, which is lower than any vintage from 2017 onwards (Figure 2). (This also implies that there is tremendous dry powder to be deployed, at the right time).

Figure 2. 2022 vintage deployment pace

With Crunchbase’s dataset, we see that the number of rounds at each stage continues to decrease. There were only 224 Series Bs globally in Q3 2024 (Figure 3). An annualized number of 894 is a level of Series Bs not seen since 2013 (787).

Figure 3. Quarterly Series Bs since 2019 from signalrank.ai

The recent spike in the average round sizes shows an underlying tale of two cities. AI companies are raising enormous Series Bs at punchy valuations, while the rest of the market fights for any remaining capital. Coatue demonstrated how AI investments represent c.3% of VC rounds in 2024 but 15% of total capital (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Coatue’s comparison of AI & non-AI rounds in the US in 2024

The marked slow down in Q3 also suggests that the sugary high of the GenAI hype cycle is starting to wear off. VCs have placed their bets to signal to the market & LPs their AI chops.

In fact, we will argue that most (if not all) of these VC bets are still too early. Maybe the slow down in round numbers is VCs recognizing that we are not yet at the power law vintage for AI investments?

History rhymes

It is underappreciated in Silicon Valley the extent to which Small Tech relies on Big Tech investment to drive innovation. (And it is also perhaps underappreciated in Big Tech the extent to which Big Tech itself historically relied on government investment.)

The predecessor to the internet, ARPANET (founded in 1969), was of course government funded, and laid the groundwork for packet-switched networks, allowing data to be transmitted between computers. Over time, ARPANET evolved into the internet, enabling global connectivity.

In more recent platform shifts, we have seen the same playbook, whereby a technology cycle first requires the infrastructure layer in place. The problem is that this layer is capital-intensive, requires specialized knowledge, and is controlled by a few large incumbent players who have the resources to continually invest in the best talent, research, and infrastructure.

The early days of the internet (Web 1.0) were characterized by heavy capex in networking infrastructure and fiber-optic cables. The real winners of the internet era (Web 2.0) emerged once the infrastructure was in place and stable. Companies like Google, Facebook & YouTube did not build the physical internet but built applications that ran on it.

Marc Andreessen provocatively argued this weekend that there was no Tech Bubble, but a Telecom Bubble. Om Malik estimates that $750bn evaporated when the Telecom Bubble burst. In other words, the telecoms industry built excess infrastructure on which the tech companies built their wares. Andreessen’s position feels a little too Manichean; it’s not clear how Pets.com or Webvan fit into this narrative. But the implication that the “Telecom Bubble” enabled tech is an argument we can get behind.

The cloud revolution was similarly infrastructure-heavy at the beginning. Amazon, Microsoft, and Google poured billions into building the world's most advanced data centers, giving rise to the cloud computing era. This enabled Slack, Stripe & Zoom to capitalize on this cloud infrastructure.

Again, the mobile era required huge capex investments in cellular networks, smartphone hardware and mobile operating systems from telcos & smartphone manufacturers. This enabled app developers, such as WhatsApp & Uber, to scale globally without needing to build the underlying infrastructure.

We could make similar arguments about how infrastructure investments in autonomous driving, satellite internet networks and quantum computing will ultimately enable the software layer to be built on each of these platforms.

And so it is with AI.

Over the past decade, there has been a massive push to build the underlying infrastructure for AI. Billions of dollars have flowed into the development of data centers, cloud-based machine learning platforms, and specialized hardware like Nvidia’s GPUs and Google’s TPUs. Companies like AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud dominate this space, providing the computational power and storage needed to train and deploy AI models at scale.

7GC estimates here that the Magnificent 7 (Amazon, Apple, Tesla, Google, Nvidia, Meta & Microsoft) have invested a cumulative amount of $75bn into AI/ML since 2020 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Magnificent 7 cumulative investments in AI/ML since 2020

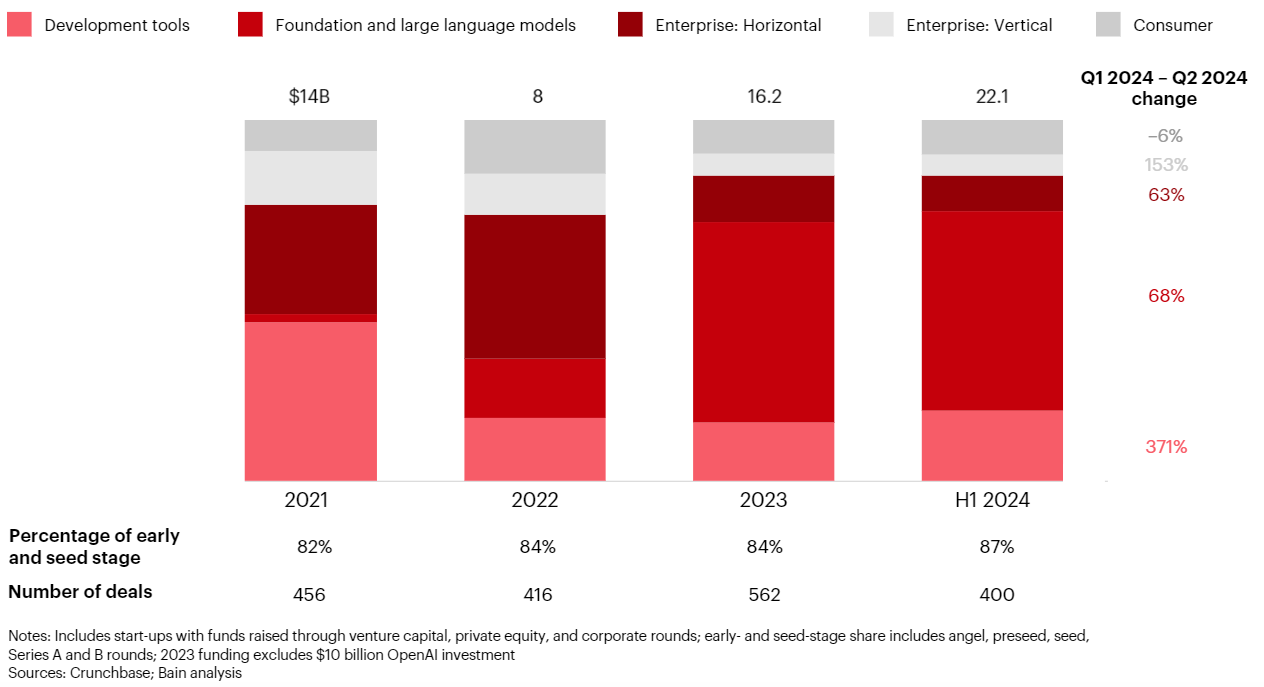

Bain demonstrates how the overwhelming amount of dollars being invested into AI in 2023 & 2024 is in foundational models (Figure 6). This is not an arena for VCs.

Figure 6. Annual generative AI funding by category ($bn)

Character.ai was an example of a VC-backed AI chatbot company seeking to compete with the hyperscalers. They raised a $150m Series A, but subsequently got kinda/sorta acquihired by Google. They abandoned the race to build large language models against better-funder competitors such as OpenAI, Amazon and Google. Here’s their new CEO: “It got insanely expensive to train frontier models . . . which is extremely difficult to finance on even a very large start-up budget.”

As such, the winners so far are largely the same tech giants that dominated other platform shifts. But the technology is still in its infancy, and yet to demonstrate the stability, standards & accepted norms required to power a software boom. For example, we still don’t understand a great deal about why transformers work so well.

So the reason we haven’t seen a clear AI VC-backed startup winner yet is because AI’s software layer is still underdeveloped. The most valuable AI applications haven’t been built yet. It’s possible that these companies are just about to be formed & funded (67% of YC’s S24 batch are “AI” companies).

Altimeter’s Brad Gerstner talks here about how:

“being early is tantamount to being wrong… [in] 1998, every VC in Silicon Valley realizes the internet is going to be big, and realizes search is important. Everyone wanted a search logo (Lycos, AltaVista, Ask Jeeves, Infoseek, Go)… You could have waited until 2004 for Google’s IPO and still captured 90% of upside ever created in search and avoided all the zeroes... Being early can be wrong. That doesn’t mean the fundamental thesis was incorrect. In fact, it was right. Internet was going to be bigger than we all thought. Search was going to be bigger than we thought. But you didn’t have to be there and pay all the high prices... We saw this in early mobile…. Same in the cloud.”

We’re potentially at a similar point in the AI cycle. A generous interpretation is to argue that VCs have learnt from history, and are holding back dollars intentionally because the real VC-backable AI business models have not yet emerged.

What does this mean for VCs?

The point of this post is that there is no easy & immediate fix to the current state of the VC industry. AI is not yet the sweeping narrative that is lifting all VC boats.

A more negative alternative (and in our view less likely) scenario is also doing the rounds at the moment, where there is a narrow aperture for VC in AI in general. This interpretation sees VC-backed companies as dancing with elephants at the AI ball. Two or three AI chat / voice companies will act as the gateway for users, dominating all layers of the stack. Software ate the world, and AI is eating software.

In truth, the unsatisfactory answer for VC is to encourage patience. If there is indeed an opportunity for startups to displace the incumbents in the AI landscape, the power law vintage(s) for AI are ahead for VCs. Maybe this comes from agentic software? Or synthetic data? Or investments in vertical SaaS companies with proprietary data yet to be hoovered up into AI systems? Or something else entirely?

Unfortunately a patient approach doesn’t really wash when you are drawing management fees having raised external capital. Capital is raised to be deployed.

Instead, VCs will have to just do the groundwork, without relying on a grand narrative. This applies to AI companies and non-AI companies alike. Find talented entrepreneurs. Help portfolio companies. Grab liquidity where you can.

And wait. For VC’s time in the AI sun is coming. It just hasn’t arrived yet.