Can you really run money on data?

Data driven VC in the broader context of quantitative finance

In 1964, at a conference in San Jose, Ransom Cook, the chairman of Wells Fargo at the time, asked John McQuown, who would go on to become the father of passive investing, whether you can “really run money on data?” McQuown’s answer led to him creating the world’s first index fund at Wells Fargo (where the fund was ultimately gobbled up by BlackRock) and to the transformation of finance. In 2024, sixty years later, passive AUM surpassed active AUM in public markets for the first time.

Today, the development of data-driven investing in the private markets is echoing its earlier arrival in the public markets. But it is early.

Venture capital has been slow to adopt data in its decision-making processes. VC has historically been an artisanal and local business. And at the earliest stages this is where we believe the center of gravity of VC is likely to remain.

Yet this is not your mama and papa’s venture capital industry. A torrent of capital has flooded into venture capital over the last decade to create an more sophisticated & deeper ecosystem. But most VCs have not changed their practices.

Many old school VCs appear to believe data will transform every industry in the world, except their own. A few renegades are changing this perception. Data-driven VCs are becoming more prevalent. An AI is now making angel investments (supposedly) all by itself.

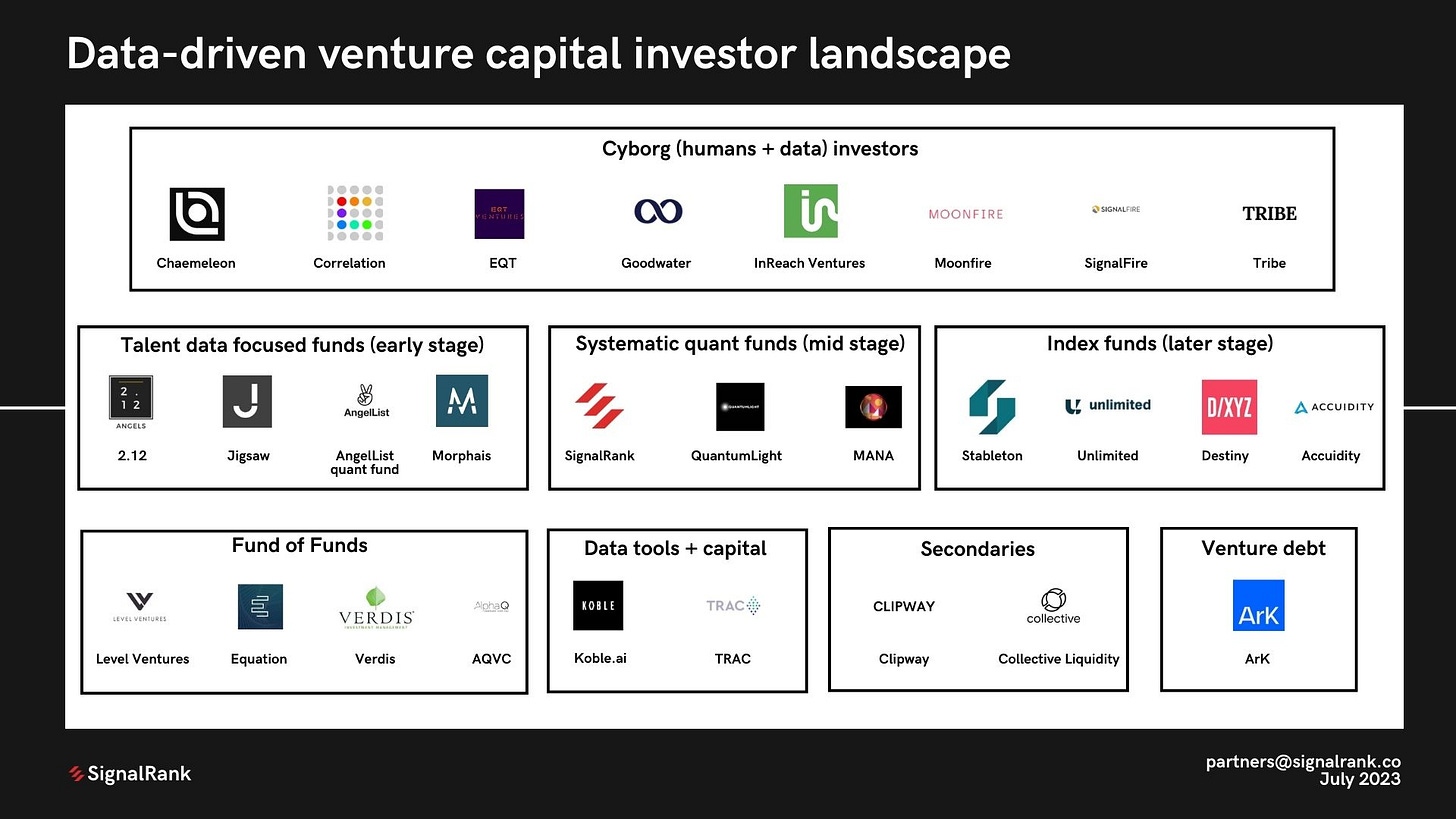

In this post, we are going to revisit some of the challenges faced by data-driven innovators in the public market, before turning to why & how different groups in venture are applying data to their craft. Like any good VC post, this will culminate in a glorious market map, in this case of the leading players in data-driven VC.

Revisiting John McQuown

John McQuown, now recognized as the father of passive investing, passed away last year. The FT had a thoughtful obituary here.

McQuown was a pioneer in demonstrating that a data-driven approach could apply to investing capital. The FT article references how McQuown explained:

“the vacuousness of the traditional methods of portfolio management, which, he pointed out, were little more than ‘ . . . a variation of the Great Man theory. A Great Man picks stocks that go up. You keep him until his picks don’t work any more and you search for another Great Man. The whole thing is a chance-driven process. It’s not systematic and there is lots we still don’t know about it and that needs study.’”

After the discussion above between the Wells Fargo chairman and McQuown in San Jose, Cook hired McQuown on the spot, enabling McQuown to turn Wells Fargo into a leader in indexing. The Wells Fargo team & advisors were an all-star cast, including six Nobel prize winners.

This is not to say that the new index was well received, including internally. McQuown said “it felt like shoveling shit against the tide. We weren’t very popular, even at Wells Fargo initially.” The broader industry was equally scathing, with the Institutional Investor magazine arguing that a data driven approach led to having “a whole army of analysts hard at work solving non-existent problems.”

This mentality evokes the Upton Sinclair quote that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” Or the classic scene in Moneyball where John Henry, as owner of the Red Sox, tells Billy Beane that “the first guy through the wall always gets bloody, always. It's the threat of not just the way of doing business, but in their minds it's threatening the game. But really what it's threatening is their livelihoods, it's threatening their jobs, it's threatening the way that they do things.”

Ultimately the quants won in the public markets. Institutional Investor even foresaw this as early as 1968:

“Not all revolutions are bloody takeovers on a day in May. Some creep up slowly. At first the guerillas roam ineffectually on the hills. Then there are a few leaders disturbingly different from those of the past. At the end their friends begin to appear everywhere in government, and you know you have to change your tune to stay alive. Investment departments are in the midst of such a silent struggle, and it is clear that the revolutionaries are going to win. Their names: the Quantifiers. Their weapon: the computer.”

Where are we with VC?

VCs focus on innovation. You would have thought that this industry would be an early adopter of data decision-making. Wrong.

In practice, VC is a people business. People (LPs) back people (GPs) to back people (entrepreneurs). Technology & markets can change quickly but people cannot. Given the length of time required for investments to mature and the lack of liquidity, it is critical to back the right people who can navigate change over time. Founders Fund‘s Delian Asparouhov outlined his approach to seed investing: “pure intuition, super obvious when you're bludgeoned by the presence of a phenomenal founder”.

Access to networks was historically localized and people-based. LPs needed to tap into the right GPs who had access to the right entrepreneurs. Communication technology has enabled a flattening of the world in terms of network development. But the irony of AI-generated content may be that a flood of pitches & introductions may actually lead to a reversion to trusted in-person networks (as articulated by Slow Ventures’ Sam Lessin here).

There is also an argument that there is little to no company-level data available at the early stages which has predictive power. By definition, the power law ensures that VC is looking for exceptions, so data from a stellar outcome may not be useful to map onto the broader ecosystem.

In this vein, this critique of company-level data-driven VC is well worth reading. The TLDR of this argument is:

Data has commoditized “thesis development” and “market research” in VC

Everyone will rely on the same research and converge on the same opportunities (defencetech! agents!)

To outperform, VCs will make “irrational” decisions based on non-quantifiable “gut-feel” (crypto again?, rocket cargo? temporal computing?)

In a world of commoditized research, human wisdom is scarce and one of the remaining competitive advantage

Winners = solo GPs and emerging managers with tight focus and industry relationships + "wisdom”

This seems reasonable to me. Why then is data becoming more relevant in VC?

It could be because there happens to be more data available. Or that LLMs & scrapers enable humans to review more opportunities (which is the breadth argument made by BlackRock’s Ali Almufti here). Or that VC is global now.

A more compelling argument in my view is that there just has to be a better way. Median VC returns are poor. LPs are exhausted from the hullabaloo of the ZIRP era. No more “proprietary dealflow” BS. No more so-called value-add platform teams. No more mythical creature names for paper marks. Enough already. Can data enable a more efficient allocation of capital to the next generation of power law companies?

How data can support VCs

Even if you don’t fully buy into the idea that data / AI can identify the next great entrepreneur, it is hard to dispute the idea that a more data-integrated investment process can increase efficiency (by removing manual and time-consuming processes), increase deal flow (by expanding sourcing and screening beyond a personal network) and reduce bias (via implementing more objective filters).

There is plenty of content on how data processes can be applied at different stages of the venture value chain / workflow. Earlybird’s Andre Retterath has quickly established himself as the thought leader in this space, having built a vibrant community and content repository here on this topic. He points to 190 firms which have integrated some level of data-driven component to their process (with at least one engineer at each firm and a proven ability to develop internal tools; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Andre Retterath’s list of data-driven VCs in 2024

Retterath goes on to argue that the VC investment process is broken at every stage, where data has the potential to deliver tangible improvements (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Retterath argues that the VC investment process is broken at every stage

A market map for data-driven VCs

At SignalRank, we have three differentiators relative to most other data-driven VCs:

we exclusively look at investor level data, not company level data (as persistence ensures investor participation has predictive power)

most data-driven VCs are leveraging data for sourcing and/or diligence workstreams. SignalRank uses data for selection / investment decisions itself (with human diligence thereafter to verify facts required for the model)

we are building an index which requires 30 investments per year, thereby approximating the mean of the target qualifying Series Bs. This is a smart beta strategy instead of an alpha seeking strategy supported by data.

The data-driven VC world is so young that it is hard to build a market map on the above dimensions. A more useful segmentation today of the data-driven VC market is between cyborg investors (investors who layer their own human diligence onto data canvases) and systematic purists.

Most VCs are dipping their toes in the water when it comes to the application of data in their process. Of the VCs who use data more extensively, most are cyborg investors (Figure 3). The positioning is more “we can do more with data” rather than “we redesigned venture around data”. There are currently few systematic purists.

Floodgate’s Mike Maples observed while on stage with a multi-stage firm: “we’re in the same industry,” he said, “but we’re no longer in the same business.” He was comparing a seed manager (alpha seeking artisan) with a multi-stage fund (beta-like asset manager). But the same could be said about the distinction between cyborg investors (alpha seeking) and systematic purists (beta-like).

Figure 3. SignalRank’s illustrative data-driven VC landscape (from 2023)

The mid to late stage systematic funds in VC (including SignalRank) tend to take their cues more from the positioning of passive public market indices than they do from VC itself. The pitch is designed more for investors seeking to allocate to venture for the first time than for seasoned LP pros. Indeed, the offer is low cost access to high quality VC at scale. In other words, these indices are aiming to offer in the private markets what McQuown and his crew started to offer in the public markets in the 1960s.

Good stuff. Love to see it.