What a time to be alive. If watching SpaceX ’s chopsticks collect a rocket going half the speed of sound doesn’t stir to you to the core, go touch some grass. The cheering and whooping of the mission-driven SpaceX team is hugely inspiring.

From space exploration to autonomous vehicles to gene editing and quantum computing, it feels like we are at the dawn of a new technology era. Peter Thiel has long complained about the slow pace of innovation in our time. This could be about to change. After the successful Starship launch, Marc Andreessen tweeted that “we are emerging from a long period of collective forced demoralization, blinking in the sunlight of profound and ambitious achievement. 👀☀️.” Behold the vibe shift.

Underpinning many of these advances is the fundamental technology of machine learning / artificial intelligence. And in this field, the United States is currently the undisputed champion. The vibrant “Silicon Valley” ecosystem, which powerfully combines capital depth, talent density & social freedom, cannot be beaten in terms of delivering innovation at scale. It’s a machine that is absolutely humming.

Let’s consider the US position in AI through the prisms of capital, talent & regulation, before reviewing efforts across the globe to try to catch up.

USA, USA, USA

The US dominates the downstream AI value chain.

It is true that chip raw materials, goods (including lithography tools from Europe’s ASML) and production primarily come from elsewhere. (Notwithstanding the CHIPS Act’s potential impact on reducing reliance on TSMC; Arizona’s TSMC plant even appears to match Taiwan’s yield now.)

But from semiconductor design to cloud infrastructure to foundational models and ultimately AI applications and services, the US reigns supreme. NVIDIA is clearly the leader in terms of chip design with its $3.5tn market cap (about the same as the entire UK stock market). The US has about 85% market share for cloud hyper scalers. Of the 101 AI models considered notable by the Stanford University AI Index, 61 are from US companies.

This dominance is made possible by winning the talent war. The United States remains the top destination for top-tier AI talent to work. A new study by think tank Marco Polo, run by the Paulson Institute, shows that the US is home to 60% of top AI institutions, and the US remains by far the leading destination for elite AI talent at 57% of the total, compared with China at 12%. The Biden administration has pushed the talent agenda further, signing an executive order in November 2023 which aimed at easing immigration rules to allow more AI experts to study and work in the United States.

In terms of capital invested into AI, there is no comparison to the US. According to this excellent piece, we are currently witnessing the “greatest capital allocation project in human history” to AI. 7GC estimates here that the Magnificent 7 (Amazon, Apple, Tesla, Google, NVIDIA, Meta & Microsoft) alone have invested a cumulative amount of $75bn into AI/ML since 2020. And that is before we consider VC investments into emerging players. Accel (in their Euroscape report) has created this useful table (Figure 1) on how there are three leagues emerging of AI players – 100% of the first two tables are US companies.

Figure 1. Accel’s three AI leagues

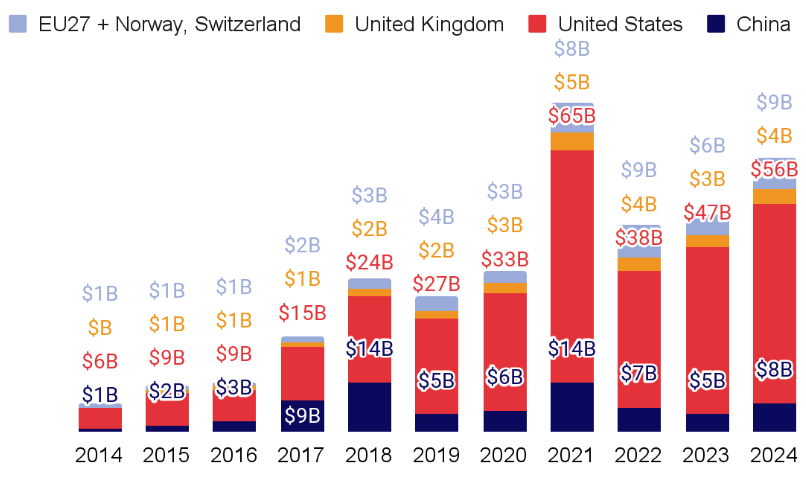

In Air Street Capital’s 2024 State of AI report (always essential reading), we see that US investment into AI has already hit $56bn in 2024 which dwarves $13bn in Europe or $8bn in China. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. US vs EU Generative AI Funding

From a regulatory perspective, the US remains broadly on the side of innovation. At the federal level, the US introduced limited frontier rules model rules by executive order (EO 14110) in October 2023. At the state level, Gavin Newsom, California’s governor, recently passed a flurry of new AI laws but did veto SB 1047 which would have made tech companies liable for harm caused by AI models (similar to the EU AI Act already passed in Europe).

Europe: Y Combinator without the equity

This started off as a somewhat negative post about how Europe has an AI problem. But then I read Harry Stebbings’ recent quote in TechCrunch about how he’s “really fed up of everyone shitting on Europe. We have unbelievable companies, and we have incredible people. We need to make Europe great again. MEGA!”. Nice. Still, Europe really does have an AI problem. Particularly a talent problem.

Europe has been an unbelievable factory of AI talent. Europe has slightly more AI professionals than the United States does (in 2023, 120,000 versus 112,000). However, while 22 percent of the world’s leading AI researchers studied in Europe, only 14 percent continue to work in the region (per McKinsey’s data).

The issue is Europe is struggling to keep its AI folk. This is not a new problem – the godfather of AI, Geoffrey Hinton, left the UK in the 1980s for the US because the UK universities would not fund his research. But it’s gone from being a trickle to a flood. World-class US AI companies are stuffed full of European AI leaders, from Yann LeCun (Meta) to Mira Murati (formerly OpenAI) to Mustafa Suleyman (Microsoft) to Clement Delangue (Hugging Face). And on. And on.

Compensation is a driver. In 2023, salaries for software developers in the United States were two to four times higher than those of their European counterparts. Menlo Ventures recently published this chart on the levels of equity offers to the top 1% of AI/ML talent in the US (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Recent equity offers extended to the top 1% of AI talent

It’s not just people. It’s companies too, as Europe lacks the capital depth. DeepMind was acquired by Google, as the British team decided they wanted an unlimited balance sheet from their US parent. A similar dilemma now faces France’s Mistral. The Information is openly talking about how Mistral is a takeover target. Emmanuel Macron is currently saying “non”. He wants Mistral to remain independent. So does the company spokesperson: “We are an independent company and intend to remain so.” But for how long? Without a powerful French/European sovereign wealth fund or a deep pocketed Magnificent 7 partner, time is ticking on Mistral’s life as an independent company.

This is also happening at the Little Tech level too. The UK’s Entrepreneur First incubator now actively encourages its graduating companies from around the world to move to SF. The default move for ambitious AI companies seeking capital depth & talent density is to move to the US. See 11x (a Harry Stebbings portfolio company) moving from the UK to the US. Poolside (also a Harry Stebbings portfolio company), flirted with the idea of moving from the US to France, and the decided they should stay in the US after all.

And this is before we talk about the Europeans’ penchant for regulation (including the EU AI Act, see Figure 4). Too much to cover here. That’s probably a focus for a future post.

Figure 4. EU regulation up and to the right: # of AI-related regulations in the EU, 2017-23

In essence, Europe is like Y Combinator without the equity. Great at spurring innovation but terrible at monetizing it. This is not to say that Harry et al can’t change Europe to become MEGA. But it will take time. All while the US marches on.

China: domestic AI champion wanted

China has been ramping up its homegrown AI industry, but it is still impacted by a dependence on US chips.

In some areas of AI research, China is already the global leader (Figure 5). Chinese researchers are already pumping out the highest number of aggregate research papers. Chinese research is particularly focused on robotics and computer vision (compared to the US which has been more focused on natural language processing).

Figure 5. AI research by country

China is the #2 globally in terms of developing foundational models. Since 2019, the US has developed 182 foundational models, followed by China (30) and the UK (21).

The ongoing strategic competition between the US and China has impacted Chinese development of its AI industry. In particular, the US has restricted the exporting of cutting-edge AI chips (read NVIDIA) to China, as well as the use of chip manufacturing equipment (read TSMC), which impacts the training of foundational models. This current dependence on foreign hardware is a core vulnerability of the Chinese AI stack today. This environment is likely to lead to a parallel Chinese ecosystem which develops along a different path to the US model (with Chinese AI based on Huawei or SMIC chips, vs NVIDIA chips).

China is yet to have its ChatGPT moment (with ChatGPT itself banned in China), showing consumers the capabilities of gen AI at large. There is currently no dominant generative AI contender to OpenAI within Chinese tech companies. In fact, many of the Chinese models are currently forks of open source Llama. 01.AI, a high profile AI unicorn, faced some backlash after it was found that their model Yi-34B was built on Meta’s system. That said, Chinese models (including those of Baidu & Huawei) are now said to be as capable as GPT4 in most areas.

There is also much more political sensitivity about AI-generated content in China, where images and text must align with the “core values of socialism”, as well as not undermining state authority, harming national unity or spreading false information. This monitoring & censorship has undoubtedly acted as a brake on generative AI platforms in China. One company, iFlytek, saw its shares plummet after its AI tablet generated an essay which was critical of Mao Zedong.

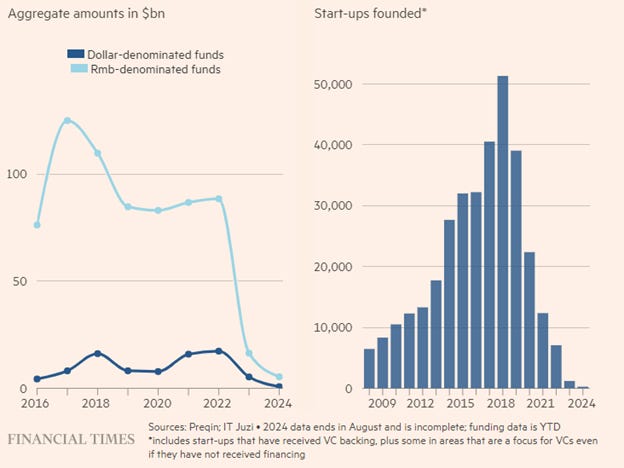

The arrival of generative AI at large comes at a particularly challenging time for the Chinese tech ecosystem. The FT recently published this much shared chart (Figure 6) on the collapse in founding & funding of Chinese startups. Even if this is only somewhat accurate, it depicts a major setback for the private Chinese tech ecosystem.

Figure 6. Chinese founding & funding of startups

The combined risk of developing an AI system which creates politically unacceptable content, plus the prohibitive cost of developing foundational models, means you can see why the Chinese models are behind the US for now. China’s (now former) minister of science and technology Wang Zhigang even acknowledged as such in March 2023 at the annual parliamentary meeting when he used a soccer analogy to describe ChatGPT’s big lead over Chinese AI products: “Playing football involves dribbling and shooting, but it’s not easy to be as good as Messi.”

But this is just today. The Chinese are likely to be very competitive in short order. Leopold Aschenbrenner’s bombastic Situational Awareness outlines how he expects China to catch up, at least on compute, power generation & algorithms very quickly.

Middle East: seeking a post-hydrocarbon future

Middle Eastern powers are keen for AI to be a core plank in the development of their post-hydrocarbon economies.

Significant dollars are being put to work to this effect. In Saudi Arabia, PIF has launched a dedicated AI fund called the Saudi Company for Artificial Intelligence, or SCAI. There is talk of a $40bn partnership with Andreessen Horowitz to invest into AI. Meanwhile Abu Dhabi created MGX, a technology investment partnership with Mubadala and G42 as the foundational partners. MGX has already announced an AI infrastructure partnership with BlackRock & Microsoft, aiming to raise up to $100bn for data centers and other AI infrastructure. So cash ain’t the problem.

However, a challenge for homegrown Middle Eastern AI efforts has been that the Middle East has got caught up in the broader competition between the US & China. In particular, the US Commerce Department had previously slowed the shipping of advanced chips to the Middle East based on fears that chips could leak to China & Russia. G42, a UAE-based AI company with historic ties to China, had been a focus of those concerns. More recently, these restrictions appear to have been eased and G42 is now distancing itself from China (including by allowing Microsoft to invest $1.5bn into the company).

Some concluding thoughts

The US election is upon us. BlackRock’s Larry Fink has said that the US election “doesn’t matter” for financial markets. And so it may be when it comes to AI – neither candidate has illuminated positions which are likely to have a major impact on the forces powering the current technology super cycle. The largest companies in the world, VCs and increasingly government itself have incentives to scale AI. The US is likely to continue to dominate AI in the short term regardless of the election outcome. There is a bipartisan inability to screw this up too badly in the short term (especially with a likely split Congress).

A more positive framing is that there appears to have been a rapprochement between Silicon Valley and US national interests. This is in substance as well as in tone. Gone are the antagonistic days of the Google employee protests about supplying cloud infrastructure to support national defense. Instead, global political instability, alongside the perceived (real or otherwise) strategic threat from China, has led to a closer proximity between Silicon Valley and government. See the renaissance in defense investments (with Anduril as the poster child). Superintelligence is considered a national security priority, with the US building the AI equivalent of the nuclear umbrella for the US & her allies.

You might argue that this proximity (or at least the lack of antagonism) between tech & government is not surprising. Tech has done all the easy stuff (social media, taxi apps, gaming etc). Now, alignment with government is required to innovate with AI in more highly regulated industries, from energy to healthcare and, yes, defense.

A perceived external threat appears to benefit the US innovation ecosystem. The Chip War is essential reading on this topic. The Sputnik effect on the US cannot be underestimated in the 1950s and 1960s, while the 1980s saw fear of Japanese semiconductors eclipsing the US (which led to a change to the Prudent Man Rule that led to US pension funds investing more aggressively into VC). And today we have China.

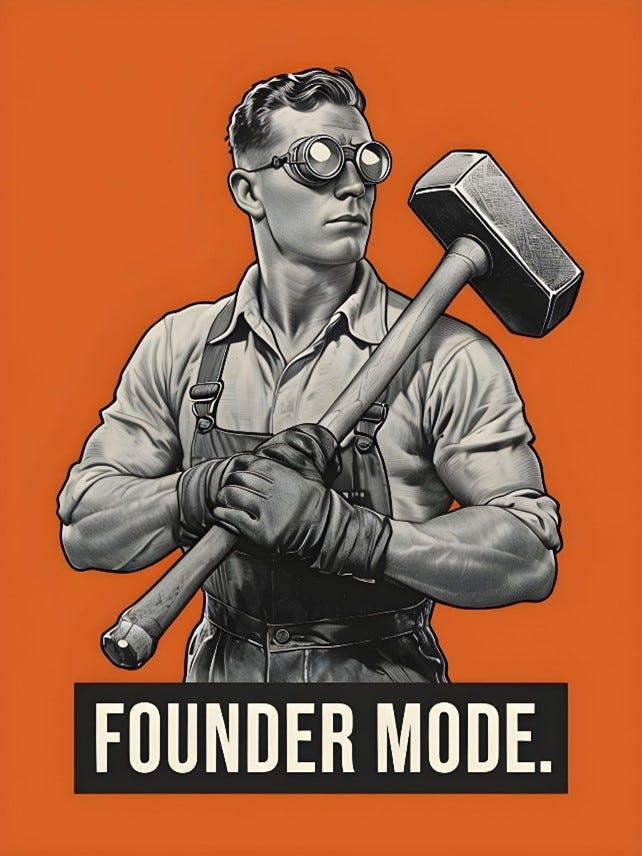

It is particularly noteworthy that the push today to create products which are positively in the American interest appears to be coming from VCs themselves. See A16Z’s American Dynamism fund. Or the Founders Fund videos reminiscing about the 80s and 90s when the US was winning. It’s not just the more right-leaning VCs either. Consider the Rosie the Riveter evoking posters in the Y Combinator offices (Figure 7). Y Combinator incidentally just backed their first cruise missile company. There appears to be alignment once again between the strategic interests of the US and her innovation ecosystem. You have to believe that this will lead to greater acceleration in technology advances.

Figure 7. Y Combinator office posters echo a more militaristic tone in US tech today

At least in the US. For everyone else, policymakers should re-read Josh Lerner’s surprisingly enjoyable Boulevards of Broken Dreams to eke out new insights about why every government in the world has tried to recreate Silicon Valley and why every government in the world has (so far) failed.